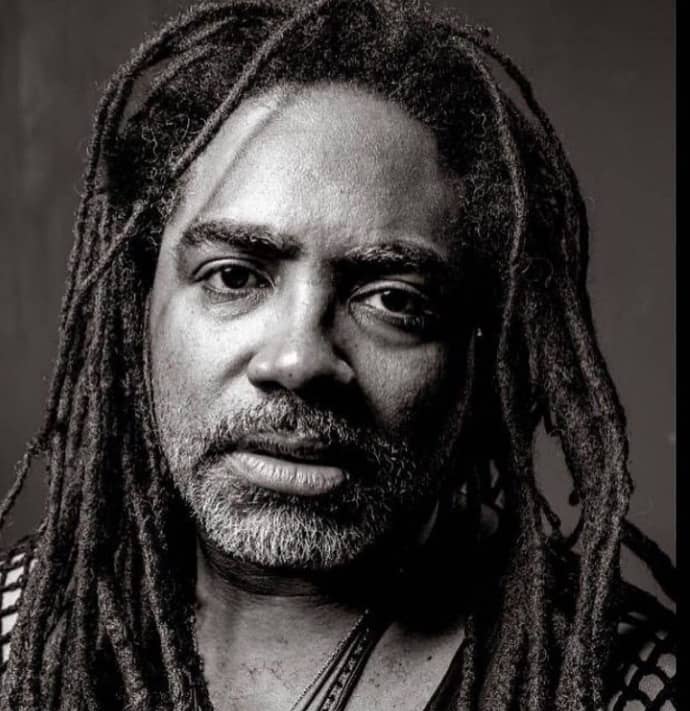

“Coz the ring you know, it was shooting the fireworks up in there, I had the Mardi Gras on, I was like if I don’t get this ring back to this person I am going to have a DOA certificate on my toe from either him or one of these guys” says Castro founder and creative director of Castro NYC and purveyor of the best jewellery related anecdotes I have heard in an age. It is not often a cocktail ring is the potential catalyst of a crime scene, but when it is made by a man whose aesthetic is instantly recognizable, who revels in using a multitude of techniques, metals and gemstones in any given piece and has a devoted clientele located on all corner of the globe it is somewhat unsurprising. Over the course of our conversation, there is a predestined mixed with self-determined energy as Castro’s story unfolds. He has first and foremost charted his own path, seemingly unconcerned by popularity or being accepted warmly into the industry’s embrace. Of his name, which sounds like a brand already he says “I’ve been Castro since I was a little kid, it’s my last name and my grandfather believed that the last name was more important than the first because it is the one that carries on.” He gives as way of explanation. For Castro, his work is a response to a deeper call, one where he maintains the youthful enthusiasm but also continues to test, challenge and push the limits of his craft. “I watched a documentary about Basquiat and it was saying that what made his art amazing was he would create from a point of view of almost like an adolescent.” Castro also possesses a joie de vivre about his work, that has taken him on a quest across continents seeking truths about heritage, creativity and art.

Nomenclature and Other Stories

“I am a creator. Or a builder, I guess I could say that” Castro notes. Nomenclature, both in how you present yourself and the industry perceives you has become increasingly important for those working in jewellery. Add the word ‘artist’ and galleries flock as your work is deemed collectable, throw in the word ‘designer’ and you run the risk of being perceived as a mere ‘seasonal’ practitioner, like those work in fashion who are governed by the weathervane of trends. “I’m trying to make at the highest possible level” explains Castro. And sometimes that leads to frustrations from clients or indeed stockists, a state of affairs he is refreshingly unapologetic about: “we have been working these earrings for like, one year, and they [the shops and clients] are so used to mapping things out, but I am like you know, my thing starts with a dream. It’s a vision and sometimes I have to see it the whole way through.” In an age where some creatives are only recently educating themselves or their clients on the benefits of consuming less, and trusting and respecting a slower pace of production, Castro had it ingrained in his creative process from the start.

It was passion that drew Castro to jewellery. “In the beginning I actually wanted to possess some jewellery” he says with a throaty chuckle, “and then I met this guy who had a jewellery store, a big j and I was like how do I get in? And he was like well, why don’t you go to school and learn how to repair jewelry because this is the bread and butter of every jewellery store.” This seemingly inauspicious beginning was in fact the bedrock for his practice, as by mastering how to repair, he had to dismantle, and it is in the recalibration of old pieces that new methods of creating evolved. His first piece was in essence a customization, the aforementioned cocktail ring that landed him in a sticky situation in a dive bar, but it set him on a path where he made pieces that he sold on a sidewalk table in Manhattan, and Castro NYC was born.

Castro is quick to point out that dramatic arcs aside his is not a modern fairytale. Whilst impressive clients were drawn to his work “one customer was like a big wig at Macy’s and another one was a big wig at Tommy Hilfiger” he says in passing, fame and accolades were never his driver. Of the initial success he notes the tension it brought with it “I felt like I am just making it for the street, I didn’t feel like I am making it for me”. To decompress, he would read, research and attend exhibitions and it was the Met Museum’s Anglomania that became a turning point in his career. He reminisces “And so one of my clients was like why don’t you do a collection? And I was like, what is a collection? And she was like oh, so you love skulls, so why don’t you look up the word ‘skull’?” Back at the Met he notes “ there was one piece in there it was a rabbit skull and it had this cool like quartz crystal on top and if I am correct I think it was rutilated quartz and it had this wire wrapping around it and I was like that is fucking incredible. And I remember I called my guy and I was like, I want ALL animal skulls. And at that moment I was like I want animals, everyone does humans so it became human and animal skulls mixed together.” The piece he is describing was by Shaun Leane, and although Castro himself tries to avoid being overtly inspired by others work “they say never look” the visual motifs coagulated with his desire to make items that were not governed solely by commercial concerns.

The decision paid off but not without challenges, particularly in how the jewellery industry would place him. On first name terms with the creative directors and founders of Taffin and Hemmerle respectively “my boy James de Givenchy, he’s amazing, I have been in his studio, we’ve hung out. And Christian you know, I talk to him sometimes” Castro has nevertheless faced the unconscious bias that manifests in incredulity that he as a black man could have conceived and made his pieces. He reflects: “The first time I had an interview with Barney’s back in the day the lady was like, Oh God when I walked in we thought you were some skinny white dude with a bunch of tattoos because it was back with the skulls collections.” That certain aesthetics or artistic concerns or methodologies should be the domain of or ascribed to a particular race is in many ways absurd. But it also speaks to how systemic racism can rear its head in even innocuous settings, and demand that a black artist must first clarify, justify and expand on the locus of concerns that govern their work. It is also illustrative of the challenges of how audiences in turn might receive black artists’ work. And whilst there is nothing in Castro’s manner that is indicative of a muzzled soul, he does pragmatically add “at one point I didn’t want my face shown because I was afraid it might affect the sales.” It is also indicative of how in many ways there is still a great amount of campaigning, lobbying and interventions to be done in terms of perceptions vis-à-vis race and what true inclusiveness will look like, even if artists themselves are willing and open to accept one another’s work on its own terms.

Who’s Design Language Is It Anyway?

Lazy assumptions are real. And no more than when editors, buyers and writers are quick to distil a creator’s design language and keep it moving. This is especially the case with black or brown creatives where, even in this post-BLM moment, mere ‘engagement’ with the so-called ‘other’ is hailed as extraordinary and groundbreaking and sweeping statements go unchecked without further intellectual interrogation. Castro’s work has been described as mediaeval, gothic, fantastical and other-worldly, but asked directly he says, “If it is one word then I would say eclecticism”, which incorporates all of the above and more. His padlocks and series of be-jewelled porcelain dolls have been seized upon as heavily influenced by European heraldry, Mediterranean architecture and Byzantine religious iconography respectively, but Castro is forthright in his clarification. “As I was doing more research for example on these cathedrals, where did that influence come from in Spain? Oh, it came from the people who crossed over from Africa. So I was like, oh okay so then it is fucking African. And you (in Spain) are just doing a bad version of the original one. It is still based on the structure, on the mathematics and geometry that you didn’t have. So, I am not really doing gothic I am actually doing African. I said to myself shit, that’s even doper.” Castro’s point might seem contentious to the art historian, however it is a critical point to make. Epistemological explorations are important and will remain so for as long as the western artistic establishment continues to stubbornly ignore or minimize African contributions and to acknowledge that migration flows in both directions will result in a mélange of influences and ideas with no location having intellectual or cultural supremacy over the other.

Castro is searingly forthright when talking about race, avoiding diplomatic turns of phrase when exploring the realities of being a black man working in the rarified world of high jewellery. He adds “I personally do not think you can be black, African and your work doesn’t reflect some part of Africa or Africanism because we live in this world where we have to think about so many other things that other people don’t have to think about in a day. So, it is going to affect no matter what, you cannot escape.” Some of his pieces reflect this reality in their totality. We discuss his Zipporah Ring and Dolly and the Benin Cat ring and he expands “Those collections were dealing with the Black Death and death itself.” Of his choice of crow’s skull he notes “it meant two things of course death but it also meant life because the crows only come around when there is something to eat…With the skull itself, it is in you it is part of you, it is part of life but it is also part of death. With some black people they will see a skull and they will be like oh God, it’s voodoo and evil and I will be like well that means you’re evil too because you have a skull inside your head. You are walking around with that thing” he says laughing.

Castro often leaves space for interpretation of his pieces. From his cryptic one-word captions on his Instagram handle to the intentionally discombobulating juxtapositions of forms on a single piece. The ambiguity or mixing of metaphors allows for a wide church of admirers as each client potential and existing sees and runs with what they connect with. He expands: “the doll was a combination of the old and the new revelation of things relating back to Africa. So the Z part became Zebra and the ears are zebra ears on the bird’s skull. People think it’s a rabbit or something but I am like no, that is zebra ears. So it was the cross breeding of things. Also with the doll the relation would be with juju and the amulets are all new like people grab the cross as an amulet and it just replaced your old amulet you know.” Jewellery as talisman is almost as old as human beings’ decision to adorn their bodies with objects but in Castro’s instance he proposes a different perspective, one where there is a constant need, in this instance the feeling of protection, but that how one feels protected is open to reinterpretation. Of the moving mechanisms within the dolls and figurative representations he explains “So it is the same idea of this movement in Africa of the festivals and we’re always dancing and we’re always moving. With the masks also represent the masquerade. And the binding of the two animals in European art it is figurative it is more actual for us in West Africa it’s more abstract. There are many meanings in one piece and unless you can talk to the artist you will never know the full meaning of that piece. And it is also about people being two-faced because also in there is the mask and when you lift it up there is another face under it.” Of the pieces names he adds “the whole collection was Hebrew names and so one name is Toam and Toamis twins and so it would be twin cat-skulls or whatever. But most people didn’t know what they meant so it was more about people having names and using names but they don’t know what they mean, especially in America, people have names but we don’t know what they mean.” It is rare that pieces dare to tackle the ontology of jewelery from an African perspective and how migration be it forced or of one’s volition has affected internal and external cosmologies, but Castro does so, and makes the ideas wearable with it.

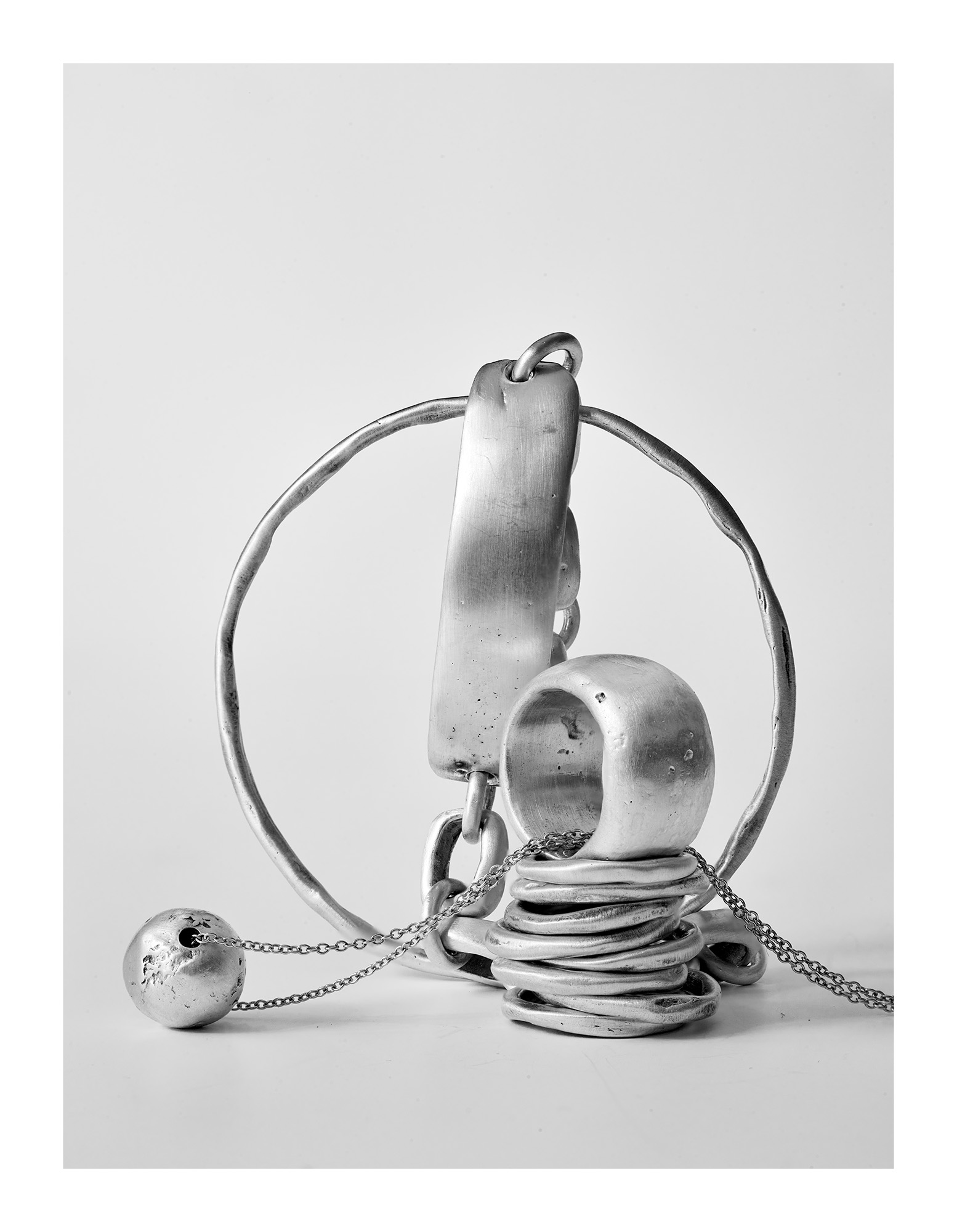

Materialism is something that has been a hallmark of Castro’s work so far with collisions of metals and gemstones that might not ordinarily be used together. However, historicism played a huge role in his initial choices: “So at the beginning I was working with brass and bronze but that is how I started and they did things that I wanted. They were like gold and they had history. Because when I went to a museum you always see when they have a jewellery exhibit there will be silver, bronze, gold. To me they were historical materials that had been around forever. So, they became my choice metals at first.” Gemstones, both semi-precious and precious came later, although he concedes “I mean I love diamonds and pearls. Pearls are tears from the moon and diamonds I love because they’re hard that’s probably one of the biggest things.” And although he has become known for his liberal use of both, it did not result in an abandonment of his initial materials of choice. “Well I think it is sort of like, when I was seeing the JAR exhibition… he had his old pieces in there and they were silver because he started with silver, but when he got big he didn’t stop – he still kept working with this material.” He notes of one of one of the most celebrated living jewellery artists whose famed exhibition in New York and London remains one of the greatest visual highpoints for jewellery lovers who were fortunate to see it. Because of his status as an autodidact in terms of creating and making, Castro allows himself to be guided principally by emotion: “I just kinda feel there is no rules within thinking of what I want. If I want to use toilet paper I will use toilet paper but I will figure out how can I make it beautiful and how can it last, because I like stuff that lasts.”

Our conversation turns to the sort of clients he has and the feelings he wants his jewellery to elicit and his answer is as ever impassioned but with additional historical and sociological analyses. “I want them to feel like rap stars, not rock stars, but rap stars. I want them to feel like a rapper I want them to feel like they’re shining. I want people to pay attention to them. And be like where the fuck did you get that? What the fuck is it? I am always trying to achieve that. I love jewellery. I might not love all rap jewellery design, but I love the idea and the idea is to shine. Rap jewellery is a metamorphosis of the 60s, 70s and early 80s where all the rhinestones were on the clothing and the idea was you were meant to be like a star. Stars shine so it just changed from the clothing to the jewellery. That’s the only difference. That’s why on the stage you sparkle, when you walk up in the club, you sparkle so I want people to have that feeling.” On a personal note the Marauder Ring was an early favourite of mine a bold gold, diamonds and sapphire cocktail ring that is a jewellery companion piece to the A Tribe Called Quest classic Midnight Marauders. Like the flow and production of the aforementioned old-school hip-hop giant, it is at once showy, jazzy, confident, contemplative and not easily placed. Similarly, Castro’s clients are people who have a strong aesthetic sensibility as his are not ‘follow the crowd’ pieces. “If it is a woman she’s got to be strong already. One of my Russian clients told me there is two kind of Russian girls. You have got the one, they come from Siberia, they find a husband and the husband, he dresses her the way he wants and that’s it. And then you have the other one who is probably married but she aint taking no shit. She’s like you gonna be fucked up. I ain’t doing no fucking bunny jumpin’ no, no , no, no! She said that is the customer I’ve got here” he finishes with another throaty chuckle. And whether the clients are Russian or from any part of the world they are the sorts of individuals who exude confidence and certainty in their decisions. Who even if they don’t work in the performing arts, possess that superstar ability to shift the energy in a room upon their arrival and exit and create a memory to even those who have a passing encounter with them.

Third Acts and Future Adventures

Although his brand name retains the city where he made his name in the jewellery world, Castro himself is now based in Istanbul. “I was kind of done with New York, I was there and I was in a hamster wheel. So I went to my storage and a folder fell out and I look and I am like’ Oh shit!’ because it has my plan before I moved to New York. And there was nothing in that plan that said get rich or die.” As well as being reminded that financial success, although it had come, was not his principal motivation, his decision to move was precipitated by the series of racially motivated murders and protests in the USA in 2014. “So we were round the African Tea Shop in Harlem and everyone was saying ‘Oh, we are going to do this and do that and they went all around the table and they said ‘what about you Castro you’ve always got something to say.’ And I said actually, I am bouncing. And they were like what? I said, I’m out. I believe the source is in Africa, and I need to go to the source. Maybe I don’t stay but I need to go to the source. I need to make a pilgrimage. I was like everyone else in America makes a pilgrimage. People go back to Italy, they go back to Ireland, to Poland or Germany. We black people are the only ones that don’t make the pilgrimage. It just doesn’t make sense.” A visit to South Africa was problematic, “they had the xenophobia thing where they were killing Africans… they reminded me of Trump people but different face, with their ‘South Africa for South Africans.” A pitstop in Istanbul has started to resemble a more permanent arrangement “my plan was just to be here for 30, 60 or 90 days and then go back. But at that time I met a lady who had a gallery named Priyo she had this gallery and she became my first customer. So, things were good because there was no need for me to leave. I decided to get an apartment just to store my stuff in and before you knew it I had a table a chair and I started building.”

New York has come back front and centre courtesy of his work featuring in Brilliant and Black the Sotheby’s New York selling exhibition that features the work of 21 black jewellery designers. The exhibition has resulted in a flurry of interviews, press calls and attention. And whilst overall the feedback for the initiative has been positive, there have been murmurings of the timing of its ideation. Is it merely a response to the summer of race protests that were triggered by the murder of George Floyd in 2020? And is it a case of a heritage auction house seeking to tick a box and keep it moving? “I am doing this because of Melanie. Melanie Grant is the glue and because of her that’s the biggest thing, it is like having Oprah’s name on it.” Castro says of the writer editor and curator who is arguably one of the most powerful black voices in the global jewellery landscape and who has activated her considerable clout and network to successfully spearhead the initiative with support from Sotheby’s jewellery specialist, Frank B. Everett. For Castro and undoubtedly the other participants, Grant’s involvement is an essential component as it is illustrative of Sotheby’s daring to do something different operationally. Heritage auction houses or any other custodian of culture have historically ignored black talent or indeed expertise. Subsequently, many black creatives have had a cautious or hesitant desire to engage because of it. However, by deferring to Grant’s knowledge as well as her established relationships and impeccable reputation, Castro observes “they were able to bring it together and that is pretty impressive”. It augurs well for future generations and for a shift in perceptions in who is included in the global jewellery canon.

There are further collaborations in development, “I can’t say who now but it’s with a stone brand let’s put it like that” is all Castro will reveal, and he continues steady production for the select stores and galleries he chooses to be stocked in. However, for Castro his work in and of itself is a visceral discourse on time’s limitations and the pursuits of perfection. “I need infinity…I want you know, the moon and it ain’t enough. I think what’s next? Learning new techniques, learning new ways and just pushing the envelope. Like every time I make a porcelain doll I am trying to figure out how can I make it more extreme. It is just a test for myself, like okay, how can I beat myself?”

Yet underpinning this goal is his ongoing love affair with jewels and making astonishing pieces. “My Mum told me that when you are in a relationship you have to go back to the beginning of what brought you two together at that moment. Whatever that is… So, it’s the same with jewellery. I have to go back to that original thing and the original thing was when I didn’t know what the hell I was doing. What was it that these people liked about me when I first started? They were looking at something where I was just creating. I wasn’t thinking about retail, I wasn’t thinking about will you like the colour, will you not like the colour. I was just creating something that I liked.” Castro’s approach is a mantra for life, whatever your chosen discipline. One where one’s vocation takes you on a series of creative adventures and there is a constant yet pleasurable questioning of what your contribution means in a wider context and how best to encapsulate passions. In his practice one sees this manifest in pieces that stand out in a crowded marketplace, that defiantly refuse to pander to trends and are collected and worn by people who are governed by a similarly singular approach to self-expression and the pursuit of beauty. In a world that has increasingly been cowed by consensus thinking and doing, artists like Castro are akin to the rarest of gemstones that illuminate, inspire and are unforgettable.