“I have always known that once you create good work and once it is authentic good work people will always come.” Says Adeju Thompson, creative director and founder of Lagos Space Programme. The brand’s debut at this year’s Milan Men’s Fashion Week was topped and tailed with a flurry of excited and laudatory press notices and more pertinently, in these economic uncertain times, global commercial interest. For Thompson who identifies as non-binary, the attention and plaudits have been novel, “I see [myself] as someone who exists on the fringe, as someone who sees themselves as part of the other,”. But although identifying as queer means many fora of existence in a CIS gendered centric world are somewhat liminal, what Thompson has unequivocally proved is that when the work is undeniable, the clothes covetable and the presentation and interpretation of ancient and current truths arresting, admiration is inevitable

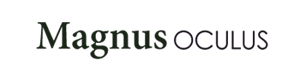

From the Collection Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet The Dress Before We Greet The Wearer, Image: Kadara Enyeasi

Creating Spaces for Different Voices

For Thompson, what started as a deeply personal aim to depict an alternative Lagos that was not steeped in the maximalist glamour and ostentation that the city has long been associated with, has evolved into a carefully curated challenging of norms and myths that have calcified into facts. They expand “It was very important that I contributed my voice..it was also important for me to create clothing from a very informed very in=depth well-researched perspective..[and] I know it is kind of weird but I felt a bit frustrated because I am someone who doesn’t like to be spoken for.” Indeed, since they founded Lagos Space Programme in 2018, the brand which takes as its raison d’être and Instagram bio the phrase ‘Sartorial Project exploring African futures’ has dared to interrogate, explore and propose alternative ways of being via the lens of apparel. Thompson not only challenges but upends many assumptions of the lived experiences of Africans and what luxury is and should be in the future. The clothes though in Milan they were shown in Men’s week are specifically non-binary and customers past and present have come from all genders Furthermore, they have dived into topics that for many of a more cautious disposition are off limits: traditional belief systems, gender norms, mental health and colonialism as a cultural decimating force have all been put under their forensic eye.

Identity, how much significance we attach to it and what it is informed by is a theme that Thompson returns to frequently: “It has become important for me to have a cultural aspect in my collections…for me, my Yoruba identity is always going to be a huge part of my work.” For Thompson, dabbling is not an option. When they choose to expand upon a thesis, they do so fulsomely. Their break-out collection in Lagos dissected what a modern-day Babalawo, or Traditional Priest would need from his clothing and resulted in an exposition for Afro-Minimalism. The collection consisted of long line sleeveless coats with multiple pockets, Adire, a traditional fabric, which Thompson has returned to severally, fashioned into wrapper skirts, and shirts and jackets occasionally adorned thin strips of reflective fabric, a hint of the futuristic possibilities that a modern diviner might be able to see. An installation at Lagos’ interdisciplinary art space, 16/16 followed, complete with a divination booth that those open and curious enough could engage with. As Thompson dared to place what has since colonialism become a marginalised practise, due to the dominant religions of Christianity and Islam viewing Babalawos as fetish and demonic, there was an inevitable backlash from those who saw the show and collection as dangerous. They reflect: “In Nigeria people are very weird [about my work] and very scared about my work. And it really breaks my heart because I am Nigerian. If only people would take time to understand where my research is coming from.” For Thompson’s part their research into ancient Ifá Priesthood divination practices showed they had more in common with computer coding and applied mathematics than barbarism. It is this reclaiming of Nigerian cultural history and placing it under a celebratory light rather than a derogatory one that drives much of their work.

This is not to say that Thompson is one for culture that is mummified. Their research always circles back to the contemporary, distilling knowledge from the past and using it as a tool to answer the challenging questions of here and now. This approach is most clearly seen in their ongoing work with Adire, a traditional Yoruba fabric, which in their hands they have defined as Post-Adire. “I find Adire itself stunningly poetic, this idea that you can tell a story on your body, like a woman will wear a print because she recently got married. This idea of subcultures passing on hidden codes within the pieces themselves, and it is only if you are part of this community that you understand…I find that idea on a surface level was very fascinating.” Thompson has experimented with different indigo dyeing techniques, a textile they also discovered had anti-inflammatory and immune system enhancing properties. Often working side by side with traditional artisans, they are reticent to use language and terms that have been popularised in the modernising textile and craft space. “I am trusting them [the artisans] to guide me… I don’t like using the word elevate. I think it is very presumptuous to say I am elevating a thousand year process. I think for me I see myself as a conduit to continue the conversation around these things..” Thus Adire prints that are still in production now, but that Thompson discovered were first created in the 16th Century, and speak to specific challenges and triumphs of then, are re-invigorated via print designs that reflect present concerns and joys.They note: “I am trying to create prints that are informed by my realities now, so dissecting ideas about queerness or mental health.” Thompson has taken the process one step further, creating knitwear from Adire, a process hitherto never done. The response has been resoundingly positive: “I am getting so much amazing feedback [and] I have hardly scratched the surface.”

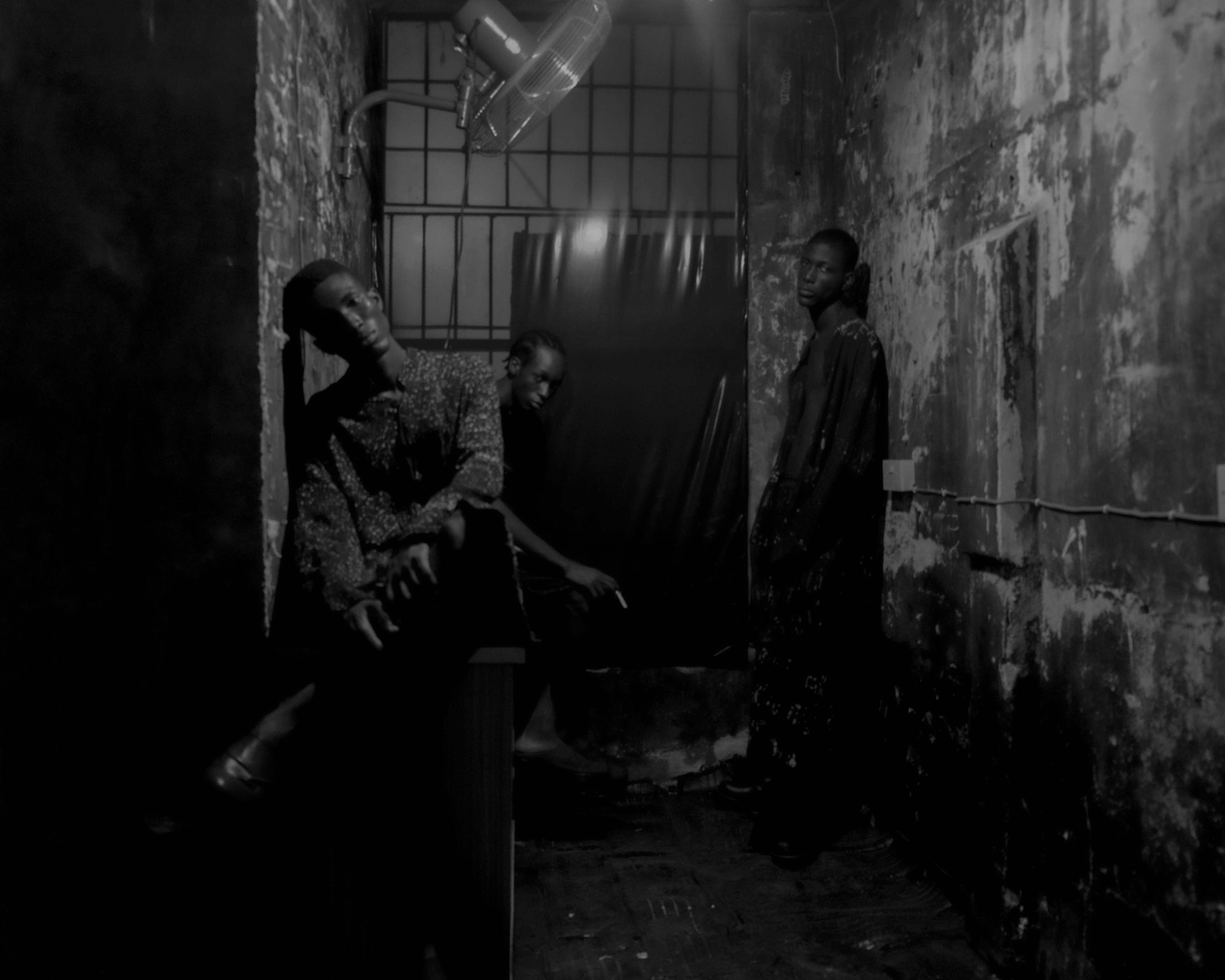

From the Collection Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet Dress Before We Greet its Wearer, Image: Kadara Enyeasi

Collaboration As A Culture

We live in the age of the omnipresent collabo, where leveraging and partnering to make a bigger splash, particularly in the luxury spaces has become de rigeur. For Thompson, collaboration has always been an intrinsic part of how they work: “I enjoy my collaborations so much because I only collaborate with people like me, people who exist and create on the fringe. My fellow nerds. It is fun because there is no ego, it is just people coming together to create.” For the recently presented collection which has the dual name of Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet The Dress Before We Greet The Wearer, the crew was a veritable who’s who of creatives across disciplines. From artist and photographer Kadara Enyeasi who shot the fashion film and look-book to interdisciplinary designer and architect Kelechi Odu who styled the collection for Arise Fashion Week’s 30/30 Show, to Seetal Solanki who played the role of muse and model for the digital diary of the trip to Osogbo Sacred Grove. Yegwa Ukpo, the pioneer menswear retailer and and unofficial mentor to Thompson was also on hand throughout the process. In each instance Thompson notes how they shared an aesthetics and intellectual shorthand with the respective individuals and drew upon their reservoir of combined talent to add further texture and nuance to the collection. Of Solanki the founder of Ma-tt-er, a platform encouraging different engagement with materials, as well as a Lecturer at the Royal College of Art and Central Saint Martin’s they note: “One thing that made the shoot with Seetal pretty incredible was the context in which I shot her in. As this woman existing in this very matriarchal space because the grove is dedicated to Osun, the goddess of fertility. So she is interacting in the grove, whether in the water or in the middle of this herd of cows, it was so freakin’ incredible and we didn’t even plan these things … But I think that is also what happens when you are working with your friends.” In the instance of their collaboration with Odu, Thompson alludes to synergies and innately understood references: “We had a pre-meeting but he just got it immediately. I was very inspired by the Comme des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto and Ann Demuelemeester shows. I wanted to give a very vulnerable experience. Because even with the models it wasn’t sexy it was very beautiful. There was a very dark element, but it wasn’t dark in a destructive way it was dark in a very sensitive way. Reflective of someone who thinks deeper about things. Those were the intersections; my identity as a Yoruba person, my queerness, and the fact that I am black.” The result was a haunting show that lingered in the memory longer than the few minutes the models were on the runway, and was one of the evening’s stand-out moments. In the instance of Enyeasi who they collaborated on both the look-book and the fashion film shown in Milan, Thompson succinctly says: “he is one of the few people I can work with and I just can leave him and go do something else because I know that whatever decisions he makes are decisions that I would like.”

From the Collection Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet Dress Before We Greet its Wearer, Image: Kadara Enyeasi

Co-creation extended to the clothing and accessories, something that has been an organic part of how Lagos Space Programme operates. The ongoing knitwear project with Alexandra Weigand’s Studio Sattelit continues to widen its locus of expression and added to the Post-Adire canon are tapestries created with Flatspot_, an artist studio based in Oakland, California and masks with London based artist David Gardner who Thompson adds “is a friend who created the masks within the realities of our shared queerness.” One of the most talked about elements of the current collection has been the jewellery and objects,cq collaboration with Dunja Herzog of Red Gold and Phillip Omodamwen a seventh generation master bronze caster based in Benin City, Southern Nigeria – a place that is seen as the spiritual home of bronze-casting in Western Africa. For Thompson and Herzog, their working engagement came about through a variety of synchronic conversations and meetings. Herzog is Swiss but came to live in Nigeria, where she rented an Afro-Modernist house designed by the iconic architect Alan Vaughan-WIlliams that acted as a salon and meeting point for creatives in Lagos, as well as a location for a Lagos Space Programme shoot. Thompson relates: “I was talking to Dunja about how my new collection was informed by clothing as spiritual objects and how I am very fascinated by the idea of designing bells for the collection, and she says ‘hold on, say no more,’ and she is rushing upstairs and bringing these series of bells she had developed herself. And it was like what? It was these two nerds nerding out in Ikoyi about bells and sound and soundscapes and the possibilities of our potential” they add laughing. Apart from the bells, staffs that could double up as wands, bangles and harness jewellery that had a modern talismanic quality to them, all designed in concert together, was the crafting process itself. It involved a road-trip to Omodamwen’s studio, where the master caster still employs the lost-wax method of casting, one which is also practised by the goldsmiths working for the Asantehene of the Ashanti in Ghana. Thompson and Herzog describe the completed collection as ‘sculptural accessories’ and the soundscapes they make in their movement is of equal import to how they adorn the bodies of the wearers. In a sense the aural effect is akin to an Emeka Ogboh, piece, only in this instance one is transported to a world of Ifá Priests and Priestesses, divination and Yoruba deities. It also reflects the collection’s title, with one ‘hearing’ the ensembles as much as ‘seeing’ them prior to greeting them. For Thompson, collaboration was also an artistic form of defiance adding: “I like that I have created my work outside of the system in Lagos and its gatekeepers. A lot of people don’t know me, don’t care about me and I literally don’t care [because] I have created my own community.” But more than that, Thompson and their ever-evolving and expanding roster of co-creators are illustrative of what collaboration should really be – a cross-fertilisation of ideas and methodologies, a playground for new ways of thinking and being and a crucible for realising beauty in it’s most undiluted sense.

Redefining Success and Luxury

Challenging what success is and educating consumers in luxury’s possibilities is one of Lagos Space Programme’s modus operandi. Prior to the Milan show, the brand was already on the international fashion community’s radar, courtesy of a full feature in Vogue in 2019; “I got that article when I was less than 800 followers (on Instagram) and it wasn’t by any connections just the strength of my work” Thompson reminisces. But although the praise party has expanded exponentially in the months since, reaching fever pitch in the last few weeks, they are adamant that they don’t want to get caught up in being the next big thing from the continent or part of “Africa Rising” narratives. For Thompson, Africa, and their locale of Nigeria, and South-Western Nigeria in particular, has always been a nexus of innovation, excellence and spiritual dynamism and these things are not contingent on praise or acknowledgement from a Western gaze.

From the Collection Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet Dress Before We Greet its Wearer, Image: Kadara Enyeasi

Value always starts with self-acknowledgement and love, and it is something that Thompson chooses to imbue their work with. For them. inspirations always emanate from what has been previously overlooked, forgotten or hidden but that is too important to remain so and they are consistently drawn to those existing on the margins. The prior collection Gay Guerrilla was inspired by the composer Julius Eastman, who died after a lengthy battle with drug addiction and mental health challenges: Thompson notes: “when I studied the life of Julius Eastman I was very struck by the similarities of our lives and a lot of my friends were cautious about how much I consumed, because there was a lot of darkness. But I told people that darkness is also part of the human condition and when I am creating a collection it is a form of therapy for me first and foremost.” With Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet The Dress Before We Greet The Wearer, Thompson was making a comment on dress as spiritual armour complete with supernatural properties. Their explorations were further augmented in an essay by the late scholar Ulli Beier, that explored similar themes, and who alongside his first wife Suzanne Wenger spent time in Nigeria in the 1960s and was part of the Sacred Art Movement in Osogbo. For Thompson the clothes and accessories are meant to have a dual role: one as luxury adornment and second as meditative aid, they add: “When you dissect my work further it is me weaving these different narratives in a way that is very seamless.” Thus Thompson’s work which straddles the medicinal, spiritual and apparel becomes desirable on numerous levels.

Thompson is keen to communicate to consumers that production takes time, is done in a human-scale with quality rather than profit in its purest sense being the driving factor and that runs of pieces will inevitably be small. In the purest capitalist sense it is a foolhardy model but it chimes perfectly in this more compassionate age we are living in, and also is a clever response to the challenge facing the luxury industry globally. If anyone who has the money can purchase an item and shareholders are demanding the maximum number are sold, how do you retain exclusivity? How do you honestly respond to the accusation of adding to the collective environmental Armageddon we are all facing? For Thompson and Lagos Space Programme, their response is to follow a conscious capitalist model; one that also places equal value on the knowledge and cultural systems that the pieces explore, the means in which they are made, and the resultant quantity produced as much as how they look on the body and how hard the tills ring in their making. Sustainability as a lifestyle is further reflected in the ordering method: the current collection is available to order until the 31st January 2021 with items sent to clients in mid May 2021. This is not fashion for those accustomed to ‘drops’ and who need to post their #ootd post-haste. Thompson adds; “The people who connect with my work, who buy the stuff, tend to be older so they are not people who go around on Social Media taking selfies, they just like wearing the clothes and getting on with their lives.” It is however, a niche without borders as clients are dotted across Africa and the globe with a particularly strong presence in the creative industries and in Europe, America and Asia.

From the Collection Aṣọ Lànkí, Kí Ató Ki Èntìyàn / We Greet Dress Before We Greet its Wearer, Image: Isabel Okoro

Whilst clothes are the starting point for Thompson they are ultimately a medium for deeper discourses something that they indicate when we conclude our conversation talking of future plans: “I envision Lagos Space Programme to be much more than a fashion brand I want it to be a research based establishment where we are contributing and adding to the conversations around African design.” `Not only have the clothes have acted as a catalyst for conversations around gender, queerness and conservative norms in Nigeria and Africa as a whole, they have also provided an important link between culture past and the current experiments that will inform culture future. That Thompson returns to motifs and methods that have centuries old provenance such as indigo dyeing, textile weaving, brass casting and divination but explores them via the lens of contemporary mores, fears and wants creates for thrilling results. That they do so in a contained palette of soothing blues is evidence of a maestro of mood evocation. In these tumultuous times we could all benefit from feeling calmer and having greater insight of where we have come from and how we wish to proceed in light of that. The brand and its founder may be young but Lagos Space Progamme’s agenda is rooted in eternal truths that Thompson aims to reveal one collection at a time to a global audience: “We are incredibly complex and we have been lied to and I think that as a designer it is my job to highlight my culture. We need to continue the conversation around these things. I feel like our ancestors would have expected us to continue the dialogues around what they started.” The oracle has spoken and the fashion world continues to listen, wear, and love it all.