Arranging a time to interview Tokyo James has proved tricky. Busy is not so much a definition but rather a default setting for the designer and fashion polymath with a career that has straddled three continents. In the end, we agree to a call in what can best be described as a multi-tasking maelstrom: James is putting finishing touches to his (now recently shown) Spring/Summer 2022 collection as well as finalising orders and deliveries for Autumn/Winter 2021. As he barks instructions in a combination of Pidgin English and Yoruba to the team in his atelier, I wonder audibly whether we will have to adjourn to a later date. “Keep talking” he enthuses breezily as he repeats guidelines to a pattern cutter, warning him of the costly implications of waste, and simultaneously tells his assistant very firmly not to accept to pay above a certain figure for fabric. “I came from a mathematics background. I came from a very analytical background, so I think I brought that mathematics into what I do I now.” James is far removed from the stereotypical fashion creative director – absorbed in himself or preoccupied with being part of the scene. He is an autodidact with a laser focus on the fiscal health of his eponymous brand. Accolades are all well and good but he is business minded and has eyes already fixed on his legacy: “I am hoping that within my lifetime I will have created a brand that will live past me.” It is as much a raison d’etre as it is a call to arms, for during the course of our conversation it becomes clear that Tokyo James is so much more than one of Africa’s leading luxury fashion houses.

Home Is Where The Style Is

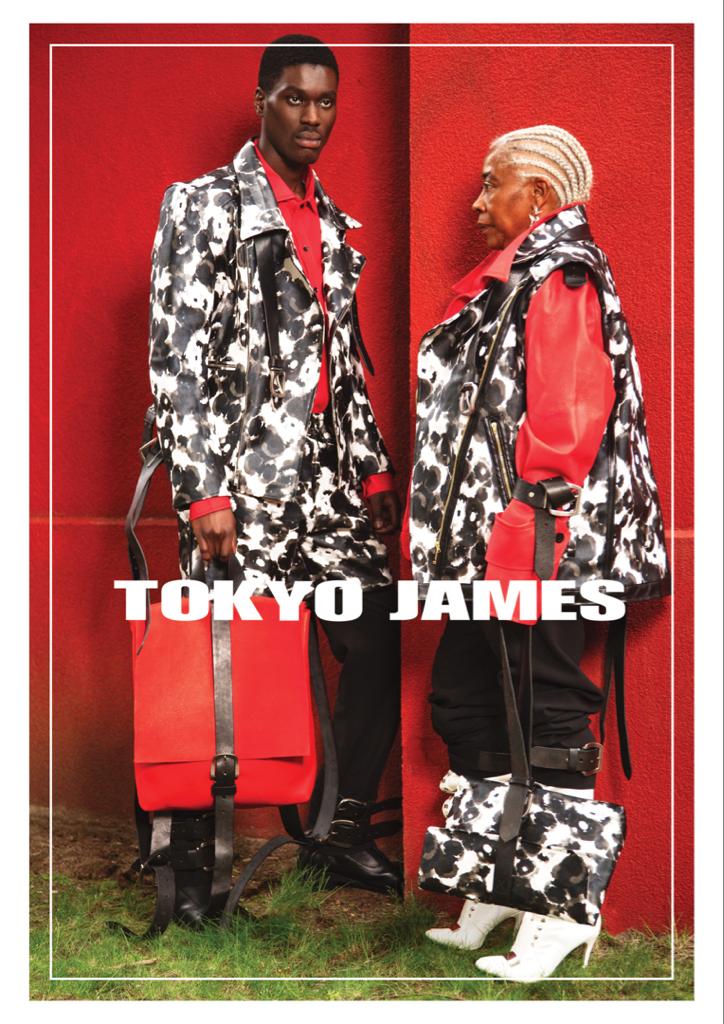

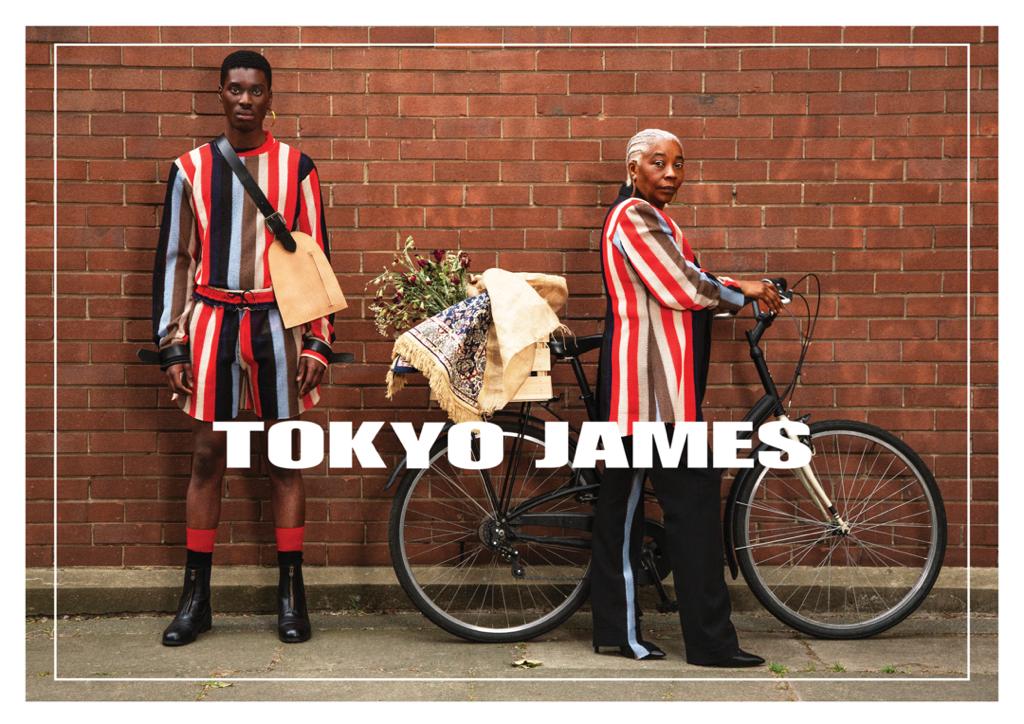

Tokyo James as a brand is a sartorial love letter to two cities that Iniye Tokyo James, to give him his full name, calls home. He elaborates: “the brand is a nexus between London and Lagos. If you’ve noticed there is a large emphasis on jackets and outerwear and that is because of London – it is cold, and I have grown up with that…. but I fused this with an African aesthetic, it is two dichotomies but that dichotomy is where the beauty lies.” James has over the years sought to upend many of the existing binaries in both locations. From the knee-jerk expectation from many in the UK fashion industry assuming that a luxury brand with a black creative director would be wedded to a streetwear aesthetic, through to assumptions that to represent the continent truthfully, clothes need to be jaunty and awash with bright, bold prints – smiling models and bongo drums on the runway an optional extra. Since his launch in 2015, James has become one of the few names on the continent who reliably offers Autumn/Winter collections that not only look autumnal but also reflect that beyond the equatorial tropical region of Africa, cold weather is present in the northern and southerly parts of the continent. And as anyone working in fashion long term will attest, clients’ lived realities and needs always anchor their clothing choices.

By virtue of his background, James has been unafraid to tackle the arguably still unresolved relationship between Nigeria and it’s former colonial master, the United Kingdom. The colonial experiment was complex, with the UK needing lengthy and protracted efforts to get the geographical area now known as Nigeria under their control, and in some regions, merely nominally. James expands: “As a brand I focus a lot on intersectionality. How do you merge two worlds together? How can these two worlds live in unison? And for me Nigeria and the UK is a perfect example…there is a lot of material to explore.” And explore he does with early collections harking back to the precision cutting found in the bastion of gentlemen’s tailoring, Savile Row but with a very necessary dollop of what can most accurately be described as Nigerian swag.

Who’s That Guy?

For someone who has worked in fashion in Europe, Africa and the Americas, where James recently collaborated with the NBA, he remains an enigma, a throwback to an era where designers took a bow at the end of the show and precious little else was known about them. By not giving too much of himself away, James has allowed for his collections to act as a window to his interior concerns and passions. It has also allowed for a wide church of clients straddling across age, profession, race and orientation, as everyone can legitimately be part of the James aesthetic and vibe. “I always say I make clothes for my boyfriend.” James says with a coquettish giggle. Adding “If my boyfriend is not going to love it then it’s a no, And my boyfriend is very masculine… I call men like him alpha males and I think there are alpha males within every set whether in the gay world or the straight world… I always say Tokyo James is for the alpha male. It could be for the alpha gay male. It could be the alpha feminine male, but you are `alpha, you are the leader of the pack.” It certainly takes a man who gives zero-fucks for ‘consumption by consensus’ to wear a red quilted hooded cape with burgundy vegan leather single breasted suit and accessorised with an oversize tote bag, a standout look from James’ Autumn/Winter 2019 collection.

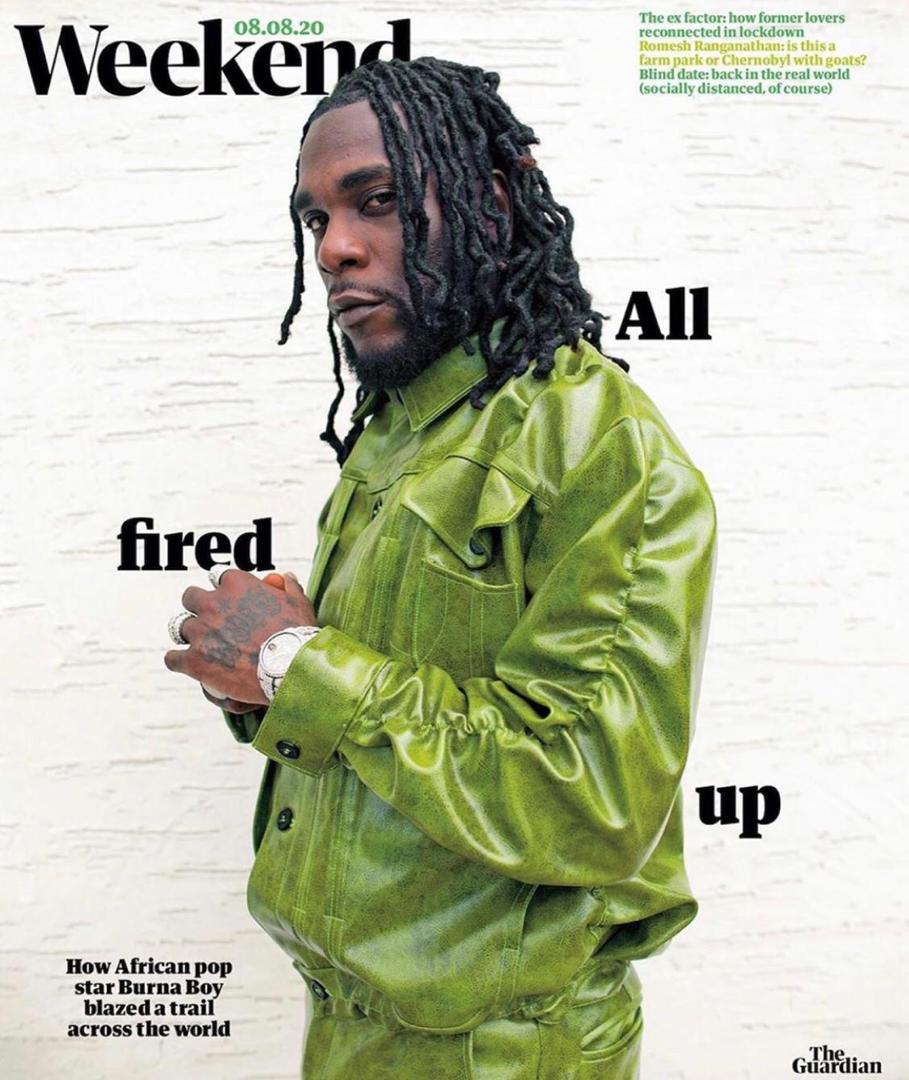

One tribe James has been indelibly associated with is musicians, of the coolest kind. James’ name was trending when Nigerian artist of the moment Burna Boy, and this year’s Grammy recipient wore custom Tokyo James to the 2020 Grammy’s where he was nominated, but surprisingly didn’t win ( he would win the following year and once more choose Tokyo James for his pre-recorded due to Covid19 restrictions performance). The three piece damask suit at the centre of a global viral fashion moment was one part ‘African Royal on Tour’ and two parts rebellious reveller who decided to pass through on an obligatory black tie event, so made sure the cut of his jib was unimpeachable and threw out the rest of the rulebook en route. “Burna has been a fan of the brand from the very beginning” is all he will provide as way of expanding on the metronome like consistency that Burna chooses to wearing his designs. Other stars have followed with singers Zlatan, PrettyBoy D-O and Rema all at one point or another dressed by the house. Further afield Chinese superstar Lay Zhang wore the Sequins Continuous lapel jacket from James’ Autumn/Winter 2021 collection and another Chinese megastar Fan Chengcheng was photographed head to toe in a customised A/W 2021 ensemble. James reflects: “It is so peculiar to me that I have started getting more love and more respect from China. A place that I have never visited in my entire life…I am so grateful [and] now I am listening to their music [and it is] making me look more and more into their world.” Can we expect the next big thing in K-Pop head to toe in Tokyo James? Given current form, probably.

Yet, in spite of the verdant possibilities of Asia and it’s elites, Tokyo James chooses to stay grounded. For every celebrity customer there are dozens of discerning but not globally recognised who return for his one of a kind point of view and keep the tills ringing. Every collection, for James is ultimately customer-centric and developing house-loyalty, like many of the heritage luxury houses of Europe can draw upon, critical. He elucidates: “It takes a lot of time [to create] luxury. It is all about attention to detail . And we pay a lot of attention towards the construction of our garments…We have a corner where I think I have cancelled garments… As a team we are like, ‘we have gone through this, tried it and it didn’t get a look’. But we do this for our customers” One can’t help but wonder that this cast-offs rack is sample-sale ready, but it is testimony to James’ meticulous approach. A foray into womenswear caused a clamour of interest, and even though he scored an immediate hit with Seyi Shay an early supporter, he decided to defer. “It is more about capacity” he offers as explanation “we are just barely meeting the demand we have for our menswear before we start catering to all the queens in the world. But we soon will.”

The Image Interpreter

James’ fashion journey did not begin with design, but as a stylist in London’s indie fashion publication scene. The 90s and early 00s were a veritable Golden Era for fashion magazines with titles such as i-D, Dazed and Confused (later known as Dazed) and Purple setting the style agenda in a potent way, unlikely to be seen again given the present dominance of digital media. “I was particularly obsessed” James reminisces with a giggle “At the time if it wasn’t Dazed and Confused I didn’t understand what people were doing…it was such experimental fashion and that was really exciting for me…I still have a large collection in my Mum’s house in London, like, stacks and stacks. I think I may have four to five years of magazines.” Given the self confessed obsession, James’ first job was as fashion director for music indie mag D101 before starting his own publication Rough (later renamed Rough Italia) “my main goal was it (Rough) had to be as good as any publication that was in existence because that was going to give me access to the next.” James mitigated the fact that he wasn’t connected to leading PRs and showrooms by “styling what I had in my wardrobe, using that to create imagery…It actually got to a situation where I had to spend my own money and buy in some of the brands that I wanted at the given time”. This guerrilla approach eventually paid off. With Rough looking the part, circulation increased, and with more eyeballs, greater opportunities.

It is here that his trajectory gets interesting: James does not shy away from talking about how the London fashion scene prior to George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 and the summer of Race Reckoning that followed, was pitilessly white with limited space for black people or other ethnic minorities to rise. James adds “There was only Edward Enninful, Pat McGrath and Naomi Campbell. Those were the only people that were in the limelight.” A career situated permanently on the periphery or stalled altogether did not suit his can-do, must-do disposition so James began plotting a way out. “Me starting my own publication was partly because I loved fashion and I loved editorial. But me starting my own brand was a result of me wanting to create iconic imagery. I wanted to style the Gucci’s and the Louis Vuitton’s, the Prada’s and the Chanel’s and put my spin and my touch on the visual aesthetics of those brands. But the opportunity never arose and so I used Tokyo James as that vehicle.”

One can hypothesise about the terrible loss to the fashion landscape had James begun his fashion styling career during a more inclusive time and bagged a styling role in a historic fashion capital working for a super-brand. Yet, his discomfiture birthed a fashion house that is greater than the sum of its parts. As a stylist – come- designer, James puts a lot of store in the brand’s visual language, ensuring messaging is clear across all touch points, with runway shows, campaign imagery and even packaging all carefully considered. In light of his first role in fashion as an image maker and then a publisher, he was quick to adopt an modus operandi that saw apparel as not only being about beautification, but also playing a critical role as cultural barometer. Our collective and individual socio-economic, political and spiritual states of mind are often revealed in the fashion of the day. Whoever, can tap in and relay that back to us wins.

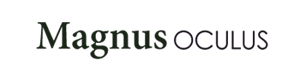

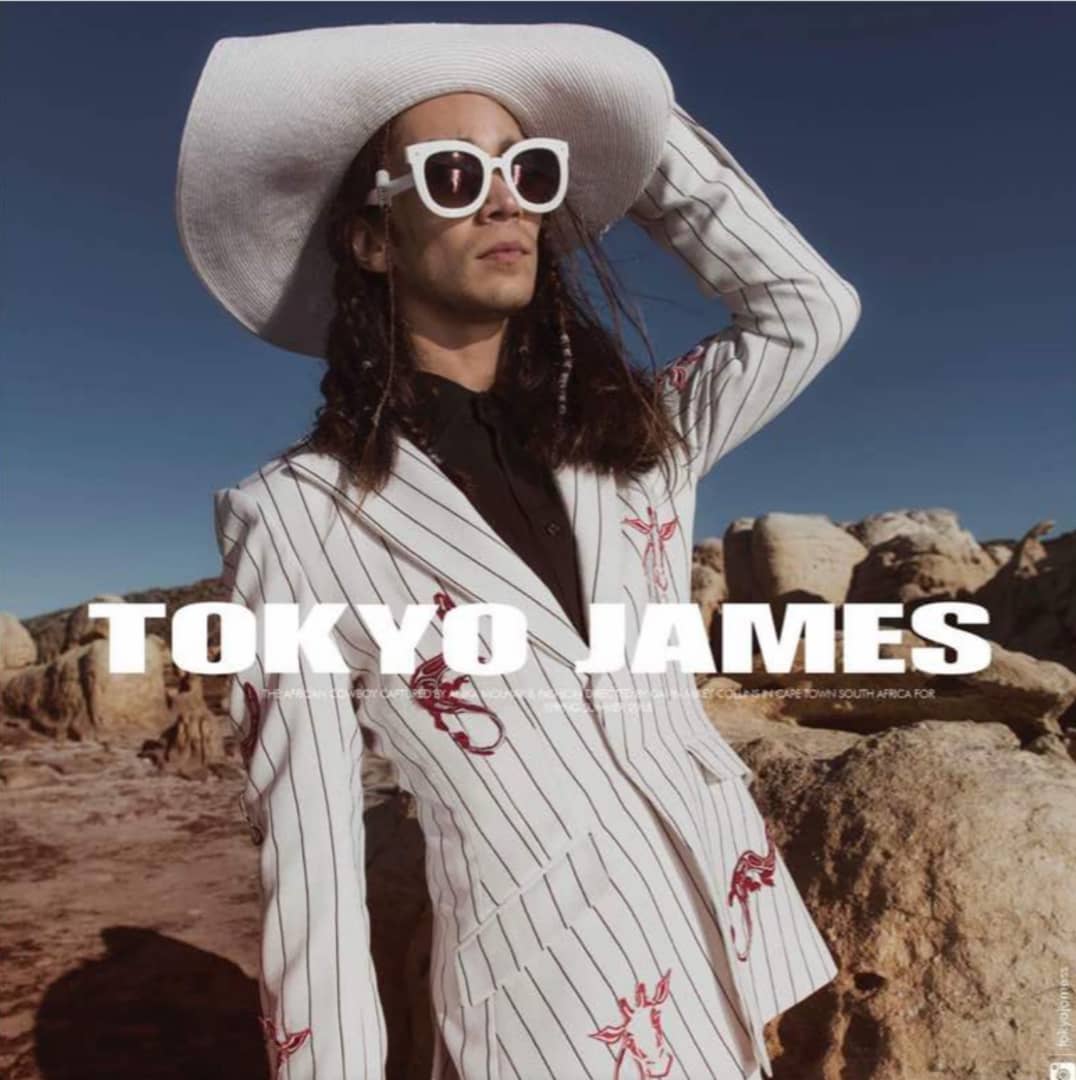

For James, collections as well as being marked by their seasonal intent often have titles where a whole thesis and bigger discourses are elicited. From his acclaimed debut at Milan Fashion Week for Autumn/Winter 2021 with a collection entitled Ogidi Okunrin which means ‘The Strong Man’ in Yoruba to the still much referenced Spring/Summer 2018 African Cowboy and his just shown, again in Milan Fashion Week Osu. Speaking of the rationale behind the nomenclature and how this manifests, James becomes particularly animated: “The African Cowboy comes from the spirit of hustle. London is a hustle and Lagos is an even bigger hustle. But the difference between the UK and Nigeria when it comes to the hustle is that Lagos is one of those places where you can be poor today and rich tomorrow.” Social mobility and the narrowing of it in the fashion industry is a topic he returns to: “I find London nepotistic, it is literally about who you know and what class you come from… In the earlier days if you were from a working class background in the United Kingdom, you had hope. But now, I don’t feel it exists as much. Because the struggle to achieve, to create anything especially for the creative is real.” James is vociferous of the dismantling of the educational grants system, the deliberate shrinking of the benefits system and the rising costs of living in the city of resulting in a balkanised creative industry. “From Alexander McQueen to John Galliano, a lot of people don’t remember that they were working class. And the system we have now, would not support them. To be from a working class background was not the end. if I was in London now, the dream of me being a designer would have died prematurely.” James translates these themes in African Cowboy via a proliferation of hats and masks in the show and suits that featured quintessentially British pinstripes but teamed them with embroidered insects and reptiles found only under African skies. He adds these “evoke the many faces you have to wear to navigate the United Kingdom and Africa.” But if you have a clear destination and a killer ensemble his thesis concludes that you will prevail.

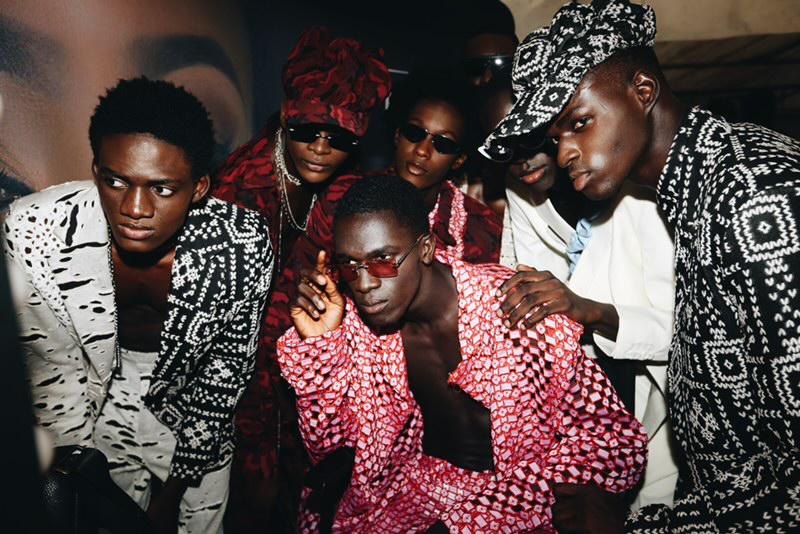

His Spring/Summer 2022 show was entitled Osu, a term from the Igbo people in South Eastern Nigeria which literally means ‘outcast’. James adds; “These were the people that they sacrificed to the gods. But I saw it as these were people who were different from the rest of society and they were actually more special.” In the James universe, the so-called freaks of society become the revered and extraordinary. And in this collection he took the unprecedented move of not using some of his house motifs. “I translated it by not using the leather which is a house signature. I translated it by using fabrics and textures that I would not normally use, so this season we used a lot of lace, and the specific lace that we used was cord lace because it has a lot of holes. First of all because of the climate but then it was also meant to signify the holes within society’s logic with a lot of things.” It also nods to traditional attire from the south-east of Nigeria which also features lace. James as ever gives a historical nod to the culture, whilst forcing it to look forward. He also played with processes. “There were a lot of distressed fabrics used and that was also to stress the affect that these actions society does has on people’s mental health.” The result was a collection that was both celebratory and poignant. Acknowledging the damage done to many whilst looking with optimism for those still left standing.

For The Love of His Community

‘It takes a village to raise a child’ says the oft repeated quote which is derived from an Igbo Proverb “oran a azu nwa”. But what if said child doesn’t fit the mould? Is LGBTQIA but not in possession of a foreign passport where a speedy exit to a life of relatively safe exile in the west is an option? Well, if you are interested in fashion, you make your way to Badore, the most dynamic fashion incubator you have never heard about and home to James’ atelier, where he has made room for many others to live, work, seek community, shelter and acceptance. “We don’t talk about it much because I just think it is very tacky how people go ‘I’m doing this and I’m serving like that’, [and] there are many gatekeepers that have used the talent of a lot gay kids in this part of the world in order to further their agendas but not really doing anything for them.”

Prior to the first global lockdown in March 2020 James invited me to Badore. Deep in the Lekki peninsula, way past Victoria Island and Lekki 1, the retail and entertainment playgrounds of Nigeria’s 1%, we arrived at an unassuming building. The space was throbbing to a soundtrack of songs one was certain would be the city’s future playlist and one was met by numerous young, enthusiastic people either busying themselves at sewing machines, sorting the bolts of fabric or putting together potential looks on fit models before presenting them for James’ consideration. In a corner, Papa Oyeyemi, creative director of Maxivive and veteran LGBTQIA activist was working on his latest collection. Whilst voices were often raised there was no aggressive energy. Perhaps because outside the walls exists the real animosity. As well as those I met on that day, Badore has played a pivotal role in the career of brands such as Vincnate, photographers such as Mike Oshai and many others who have for a variety of reasons distanced themselves from the place that gave them creative refuge. James is pragmatic: “a lot of the gatekeepers are very homophobic but pretend they are not to their western peers because they know how the western peers can shut the doors.” This results in many underplaying or even hiding their orientation for fear of negative repercussions and those said forces posing as pseudo-allies. The themes of James’ African Cowboy come to mind as people shape-shift to save face, career or whatever else they are pursuing or protecting. But James sees a positive end-game in fashion’s future,: “I do this for the younger generation so that they can see that it is not going to be easy but it’s possible.” Ever the realist, James who himself did not go to fashion school and irreverently dismisses it as “just a big networking forum”, sees his role as providing a space where those on the outside can get a tangibly beneficial ‘in’ and not become casualties of circumstance.

Beyond the Clout Chase

Whilst many luxury brands have struggled or even shuttered in light of the pandemic, Tokyo James has had a phenomenal year. Having previously shown in London, Lagos and South Africa’s Fashion Weeks, the brand added Milan to their roster. “It was another fashion week.” James deadpans before adding “of course we were excited. I think I was more excited that we showed on the same day as Prada, I was like ‘Oh My God! Prada!’” As well as the shows, there have been features on Vogue Runway and a deal inked with heritage cognac house Martell. Prior to the global lockdown a partnership with YouTube included a pop-up in London’s Westfield and Tokyo James was one of the anchor brands selected by Grace Ladoja’s Metallic for The Homecoming an online festival and retail-led event that was held at Browns London. Since Milan this year, more prestige stockists have followed including Dover Street Market: “that nod from a store like DSM is one of those things where you are like, ‘yeah, okay this is super cool.’ It is always nice to get that recognition.” When I pose the question whether the industry embrace has become a delicious experience, one that will always need to be sated, James laughs before exclaiming “Definitely not! With or without them we would have continued doing what we are doing because we believe in us.”

James is the embodiment of practical perseverance meets clarity of vision. Prior to his brand being in a position to partner with a drinks company or a tech behemoth, he dusted off his mathematics degree and with his fashion nous worked for Accelerate TV the online platform that is part of Access Bank, one of Nigeria’s largest financial institutions. “We were there to invigorate and excite he millennials” he says drolly. He was also unafraid to review how he could become more environmentally sustainable and while he was an early adaptor of the possibilities of vegan leather, he was also determined to always present customers with a choice. “It was us doing our little part to save the environment for future generations. But choice for me is essential and percentage wise customers are 75% vegan leather to 25% leather which is really good.” Self-affirmation as principal motivator and intersectionality as the happy by product is also seen in a bag he first debuted as part of the Ogidi Okunrin collection but has now gained a life of it’s own. The Ato Rodo, the Yoruba word for the Scotch Bonnet Pepper, has a ubiquitous best supporting ingredient role in Nigerian cuisine. In James; hands it has become the arm candy of choice for those who wish to have a ‘for the culture’ moment but make it fashion. The shape is immediately recognisable to those who eat the peppers and to the rest of the world it is just another cool shaped cross body bag that is capacious enough for your daily essentials.

James’ story=so-far in many ways reads like a modern day fashion fable = without the appearance of a Godmother waving a wand or indeed a wad of cash. An absence of distractions which would have been there aplenty had James been a card carrying member of the in-crowd have given him the time and space to focus on his craft. Because the African fashion scene, in spite of the flurry of positive stories still remains a relatively closed shop. Most of the successful brands across the continent have hereditary money oiling the engine and familial connections swelling the customer base. Furthermore, proximity to favourable business opportunities and access to markets is very much a chum-o-cracy, an issue highlighted in Papa Oyeyemi and Udochi Nwogu’s seminal essay for Business Of Fashion tackling bias in the industry, and the organisation they subsequently launched, Bias in African Fashion. If you don’t fit the look and feel, it can be demoralising. However, it is important to note that these issues of inclusiveness and level playing fields are present in fashion capitals in other cities too.

“I have never felt welcome in London and I have never felt welcome in Lagos” says James. Yet one could argue this has been his greatest blessing. Belonging often brings with it a rigid point of view. We have all become citizens of the world by way of our phones, but James has actually lived it too and possesses a competitive advantage in distilling this via the lens of fashion. The visually literate such as James, hold a winning hand in a world where our attention spans have been so shot to pieces and our brains rewired to seek the next quick hit via an arresting image or a catchy song. Furthermore, if we accept the fact that fashion has become a business first and foremost and a creative expression second, James’ mathematics background equip him in a way a less financially savvy designer would only dream to. There are however, some complicated yet beautiful contradictions: James is the antiestablishment outsider who nevertheless sells luxury to the cool kids of the global music industry. The loner who has opened the doors of his home and atelier to society’s misfits and ostracised. And a sensitive soul whose heart burns hot against injustices in his chosen industry. He candidly admits “I have had to fall and re-fall in love with fashion so many times,” but each time he does he falls hard. Bringing the intensity of those feelings, blending them with his innate cultural magpie sensibility and the romantic notion that all true lovers of fashion have of an epic ensemble possessing the magic to change your trajectory forever.