“I put a part of myself in each jewel and it is always a new story to write and to read” says Emmanuel Tarpin, one of the world’s most feted new talents in high jewellery. The poetic turn of phrase is in no way hyperbolic. Tarpin’s creations are not only adornment but also act as a conduit for communicating emotions, ideals and other truths. Ones that lucky wearers will have to wear and treasure forever. Serendipity may have played a role in the achievements his eponymous house has received since launching in 2017, with accolades aplenty, industry recognition, and a loyal client base. But whatever may be ascribed to good fortune and timing is underpinned by Tarpin’s own innate understanding of who he is, what he has to offer and how his processes, design language and aesthetic are pushing boundaries in what is expected in high jewellery and who can participate within that world.

In Pursuit of Beauty

Paris based Tarpin has a melodious voice and is matinee idol handsome but seemingly unaffected by it. We converse for far longer than we had initially scheduled as he admits “I could talk about jewellery all day”, but our conversation is more of a reflection of his knowledge and vivid storytelling. Tarpin is passionate and delights in exploring creativity in all its iterations, drinking deep from the experiences of travel and observing and capturing the beauty therein. “I love music, I love dance, I am crazy about classical music as well and I practised sculpture for fourteen years, mainly working with clay.” This omnivorous appetite did not diminish once he enrolled at HEAD, Geneva School of Art and Design, specialising in jewellery, accessories and watches as he reminisces “I even asked a glass blower to help me and I am always really inspired by talented people…To be curious is the best thing to be and to stay.” Intriguingly, Tarpin is also a fan the Golden Age of Disney animated films, he says laughing, “I have been indoctrinated with Disney, it has been a big part of me, I know all of them. Beauty and the Beast, Cinderella, Snow White, they taught me to keep a child-like vision about everything” Indeed there is something otherworldly about his creations, that are fit for the chicest of modern Disney Princesses.

On graduation Tarpin joined heritage house Van Cleef & Arpels, but rather than the design studio, he chose to work in the workshop. However, after three and a half years the pull to start his own eponymous line became too strong to ignore “it was really nice because [in the high jewellery department] it was only one of a kind pieces [we were making] using really amazing stones so it was the best school to learn how to make jewellery.…but I was working on pieces for them and not mine and that felt a bit frustrating” Starting his own line, especially one dedicated to high jewellery was not a decision he took lightly “of course I was a bit scared as it is always complicated when you start your own brand but it was a feeling. Because I am someone who will always try things, who likes to evolve and so, why not?” He adds with a chuckle. Much has been made of Tarpin’s youth but what is not often dwelt upon is that his was in many ways a long apprenticeship; first in his own private study and appreciation of the creative and visual arts which commenced in childhood, then in his academic endeavours and finally in founding his brand. The tired trope that his is an indecisive generation finds an elegant rebuttal in his work and attitude to it. What is also telling is his choice of word, making his decision on a metaphysical ‘feeling’ rather than one that is governed by a conventional career trajectory. When he knew it was time, he simply trusted and acted. As he points out “I think it is ridiculous to think about age as there is no specific age to express yourself and to show your inspiration.”

One might conjecture it is following his intuition, rather than what the crowd expects that has allowed Tarpin to have an avant-garde approach to his craft, experimenting with metals to stunning effect. Tarpin uses aluminium prolifically, in part because it is lightweight, he notes from his Van Cleef days, ”I worked on a big pair of earrings which were very beautiful and I remember hearing that one hour during the dinner the client had to remove them because they were too heavy and too uncomfortable for her and I believe that jewellery does not have to be like that.” However, he does not compromise on impact, choosing gemstones every bit as breathtaking as those used by the Place Vendôme stalwarts. Diamonds in all their colour iterations, Paraiba tourmalines, rubies and sapphires all feature in his work and like the German heritage brand Hemmerle he loves to play with patinas to create an additional textural layer to pieces.

Early industry recognition, courtesy of his much referenced Geranium ear pendants was testament to the dividends of developing a clear and recognisable design language. The story of how they ended up in the Christie’s Magnificent Jewels Auction in December 2017 and easily realised their reserve price has a Disney – The High Jewellery Version – ring to it. Tarpin speculatively called the auction house to come in and show his work and the ear pendants were an instant hit and vitally, a last minute addition to the catalogue. For Tarpin however, it was more reflective of a commitment to a particular aesthetic for his work “I can be inspired by a cool shape of a flower or a plant’s really small detail.” The plant’s verdant hue is mimicked by the aluminium and the round cut diamonds aren’t just an obligatory dusting of bling, but reminiscent of morning dew settling on leaves. Since the fabled Christie’s auction, Tarpin has chosen to keep his operation ‘human size’, making one-of-a-kind pieces for clientele who like him are drawn to particular and specific markers of special; “Quite often they are collectors of paintings or sculptures, they are very interested in culture..and love details…They will buy a piece because they have fallen in love with it.” Tarpin is adamant to not rest on his creative laurels and recreate pieces he has made before, even if a client requests it. Instead he ensures that energetically and aesthetically there is something of the client’s essence in the custom pieces he creates. Visits to his atelier often result in friendships as he delves deep into a client’s memories, passions and gemstone preferences, he notes” jewellery is something very intimate because it is worn very close to the body… so in this way I think it is important for it to be one of a kind as we all are…I like clients to enjoy looking at the piece, wearing it but also to see it as a beautiful object..If jewellery is an art, which I believe it is, we don’t want duplicates. Just as with a painting we need only the one. The original.” In a world driven by profit there is something romantic with how Tarpin approaches his work and treats his clients. This is not a conveyor belt exercise where celerity and efficiency reign, but a discourse, a dance between mood, cadence and connection.

The Bucolic Dream Realised in Gems

Annecy, is an Alpine city in south-eastern France and Tarpin’s home town. From the mediaeval era it changed hands between the Counts of Geneva (less than forty kilometres away) and the Dukes of Savoy whose territories stretched from modern northern Italy to south-western France. It is a city that in many ways is a chameleon with only the surrounding countryside a constant. French, Swiss and Italian in character, a refuge for fleeing Swiss Catholics during the counter-reformation, a crucible for ideation. Framed by the crystalline waters of Lake Annecy and nestled in the shadow of the Alps, the surrounding terrain has featured prominently in Tarpin’s work and continues to act as principal muse. “during my childhood we took a lot of walks in the mountains with my parents and I continue to do that because nature is a real passion for me.” The juxtaposition of beauty and danger present in the mountains is captured in Tarpin’s Foxglove ear pendants, a flower native to the area but also highly poisonous. His bejewelled version in red gold, yellow gold with a single rubelite as the dominant gemstone is the sort of piece that remains in one’s mind long after first sighting.

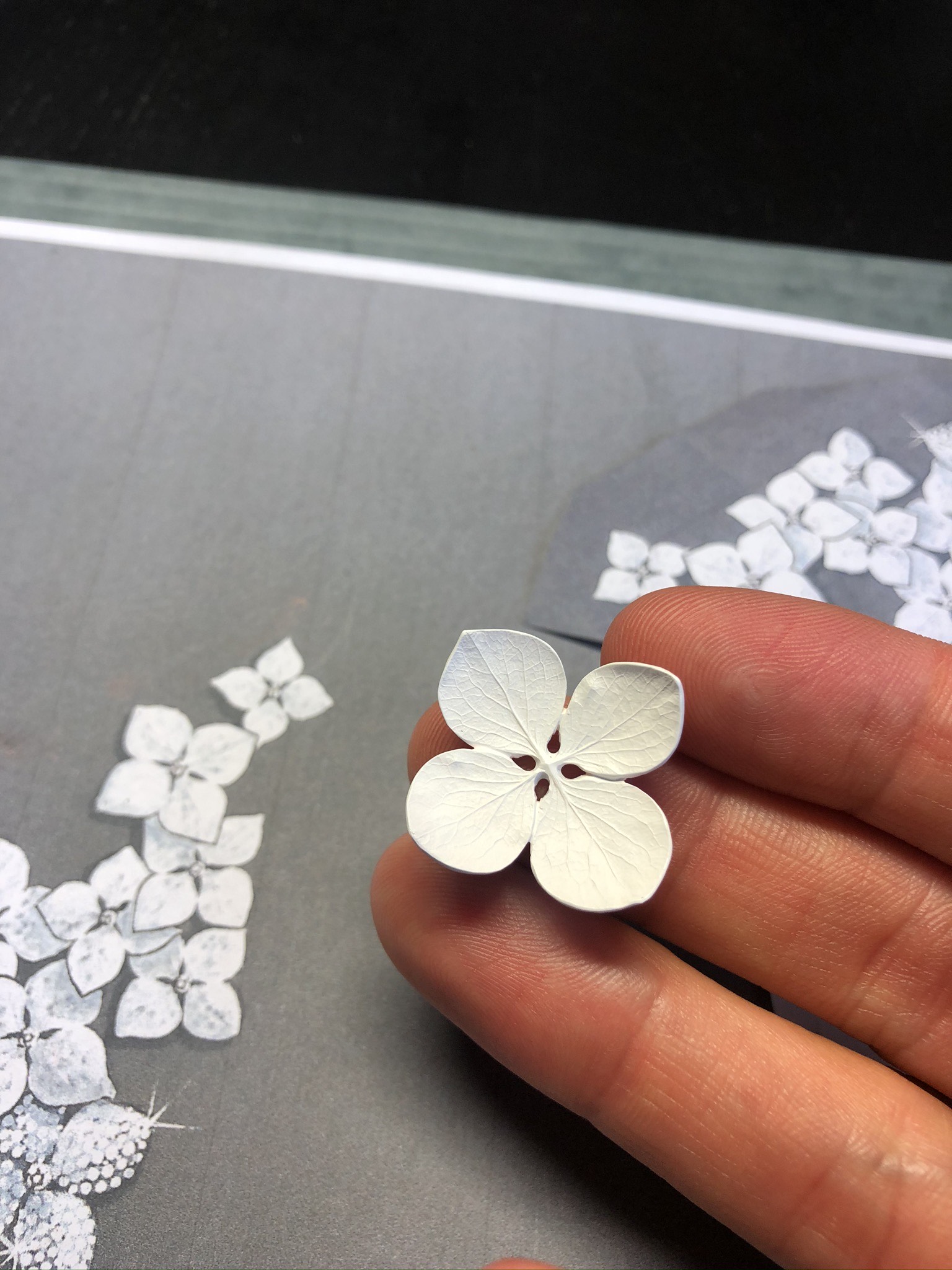

Tarpin’s use of gemstones in replicating flowers and vegetation is carefully considered. And furthermore, speaks of someone who adores wild open spaces and observing and absorbing the intricate details displayed for later use. Instead of yellow diamonds he selects yellow sapphires for the Globe ring which give an intensity of hue rather than the reflected sparkle of a canary diamond which would detract from the lush artichoke leaves with their patina. His beanstalk earrings play a similar trick, creating a coiling tendril of green garnets and tsavorites that seem to be growing from a wearer’s earlobe. Finally, an acorn brooch is an ode to Autumn, that like Keats’ famous poem one can hold close to their bosom. Although flowers are a motif many high jewellery houses return to from Van Cleef’s Quartrefoil to Chanel’s Camelia, Tarpin’s fascination with foliage, often placing it centre stage, is novel and speaks to a profound notion – one where we are called to reconsider what is valuable and what is worthy of being deemed beautiful and eulogised as such.

His family are still based in Annecy, and they are all intrepid travellers: “we travelled a lot when I was young so I saw a lot of countries.…My parents always chose to travel in the non-touristic way and I still try to travel this way”. Tarpin, a keen diver, attributes the ocean and its bounty as another enduring inspiration indelibly realised in his seashell earrings, that were worn by Rihanna. Although honoured that she chose to wear them and cognisant of the favourable attention that resulted, for Tarpin, celebrity endorsement in and of itself is not a primary motivator.”You don’t see a lot of my jewels on celebrities because I don’t produce a lot and every time it is one of a kind so chasing them will not fit my business model.” What the piece spoke of more was Tarpin’s own ideology of celebrating the natural world in all its guises but injecting modernity via the presentation, the kind that would get image savvy clients, be they famous or not, clamouring for more.

Leading High Jewellery’s Reset

High jewellery has been going through a something of an image re-boot of late, from the grand heritage houses of Place Vendôme transforming Haute Joallerie week to a companion to fashion’s Haute Couture week, to the proliferation of jeunesse doree being co-opted as brand ambassadors. Kaya Scodelario for Cartier and Lisa Manobam of Blackpink for Bulgari are two recent signings. These somewhat clumsy attempts to tap into a particular demographic are not Tarpin’s modus operandi, instead his approach is one of democratising the rules of engagement with his Instagram page playing a pivotal role. He expands: “My instagram is a window…a lot of people have told me and sometimes criticised me that it doesn’t look really professional, and I am like, I am not looking for a perfect page with jewels on a white background. I love to share final pieces of course, but I love to show my inspiration. I love to show some drawings, some different steps because I think that there are so many interesting things about jewellery.” The result is a page that is every bit as compelling as an influencer’s and a visual autobiography. Tarpin oscillates from beautiful still life drawings to images of him at his bench, to finished pieces occasionally modelled on the body, but more often than not photographed on their own. His contribution to jewellery industry and enthusiasts community, Gem X Club’s Advent calendar was a Spotify playlist, and reflected his relatable nature and his more relaxed social media approach. He adds: “I feel we have to share, and I love to show everything because it is part of my process and it is important because it is a part of me and sometimes to understand my work you have to understand me as well.”

How people engage with high jewellery is also important to Tarpin who notes “people have to see jewellery as an art and to respect it is as such,…it is not just precious stones on a metal base and that’s it, there is more than that… sometimes a client can buy a piece worth millions and not understand why the price, what took time, what is interesting about it, they will just put it in the safe and not understand the story of the jewel and I think that is really sad.” Owning an important piece is one thing, appreciating it another and still understanding how it fits in the widen canon, where Tarpin cites the work of Suzanne Belperron and Rene Lalique as being particularly influential is the final aspect in the equation. Luxury has long traded on the cost of an item rather than its intrinsic value or even its contribution to widening the remit of design. Tarpin’s methods, showing his process and the ‘tricks of the trade’, for all to see on his feed could be viewed as radical, potentially harming the market, but they are merely an expansion and acceleration of his objectives to create high jewellery and a community within it that is untethered to existing rules.

Tarpin has become a deft hand at cancelling out the noise, even if it is laudatory, “I just focus on my creations and don’t think too deeply about people’s perception or reception”. Consequently, it spares him being governed by critics’ reviews or client’s expectations, and allows him to retain what he cherishes the most, an open and uncluttered mind to channel his creativity best. He is equally as alternative in his thinking of how high jewellery should be worn as he is about how he should be received. “My clients can wear my jewels for big events with a beautiful dress by a huge designer for example but also they can wear it with a white t-shirt and a jean and the jewellery will be what creates the full outfit.” This insouciance, creating informal spaces for jewellery to be worn, taking it out of the realm of the ballroom or wedding banquet or indeed safe deposit box, is perhaps what is most revolutionary about Tarpin. Giving clients the permission to not have to wait for a special occasion but instead to make every day special by wearing their most precious pieces is thrillingly liberating.

Future Plans and Legacy Building

Tarpin’s eyes widen when I bring up the topic of legacy, “You know I am still at the beginning, I am not an old brand.” He says laughing. But it is not an entirely unexpected question given the opening four years and his prodigious talent. Unsurprisingly, Tarpin does not live and work in the city’s jewellery quarter but instead the 7th Arondissement, home of the Musee D’Orsay, Musee Rodin and the iconic Eiffel Tower. By picking a corner of Paris teeming with art and beautiful gardens, Tarpin is tapping into his perennial sources for inspiration, whilst still ensuring he is not too far off the beaten track. “I am finding a good harmony between my life and my work,” he notes and admits to savouring time spent in his much instagrammed rooftop garden tending to his plants. And although he has jeweller friends, industry gossip and the scene prior to the pandemic hold little draw. In many ways it is the recipe for a brand that will stand the test of time, as in choosing not to pander to a scene or clique he can quietly and assuredly hone his craft and deepen relationships with new and old clients who have come to understand and appreciate what he has to offer. It is however, not unreasonable to speculate that based on current form Tarpin’s star seems to be the sort that will attract a museum retrospective in the future. Maybe one as unforgettable as that held for JAR in London’s Somerset House in 2002 and New York’s Met Museum in 2013.

We close considering the shifting relevance of jewellery in society’s eyes; from the proliferation of brands, to the unrealistic expectations for production, even in the rarefied world of high jewellery where clients are accustomed to waiting. “I take my time for each piece because if I want to do things well I have to feel it.” Is Tarpin’s succinct response to those expecting speedy turnarounds. We also touch on the fact that jewellery has itself had a moment of reckoning with conversations about ethical sourcing, mining, inclusivity and environmental degradation all no longer on the periphery but central to how those in the business work today. Tarpin reflects; “Our workshop uses very ethical metals and gemstones, I have to be very careful and that is why I don’t work with a lot of gemstone dealers” The net result is sometimes sourcing a particular gemstone might take longer for a client, but in today’s climate, where reputations can rise and fall in an instant, it is worth it. Tarpin also hopes a time will come where jewellery is no longer a mere addendum of the Red Carpet, “I never saw a total outfit that was important because of the jewels.” He is equally enthusiastic about gender norms being more expansive, as they are in the global south where the notion of men bedecked in jewels is not considered subversive. Of his extensive research whilst studying in Geneva he observed “In Africa I saw a lot of pictures in the archives where the jewels mean everything and the men were wearing the most… and in India too there was jewellery that was only for men because it was a way to show power and masculinity which is contrary to its role in the west now.”

Will Tarpin takes his initial findings as a cue to create pieces that speak to this and maybe reference the savannahs, rainforests, deserts, mountains and ever changing coastline of Africa and the Indian sub-continent? One can but hope. Tarpin believes that for jewellery to have resonance for future generations “we have to think and look again at what jewellery meant in the past.” Whilst this is clearly true, the industry also needs pioneers, lodestars of taste and discourses, and innovators of craft who work with a fearless spirit. High jewellery has found one such voice in Tarpin: an artist who possesses the talent, curiosity and dedication to continue enthralling collectors, appreciators and curators for many years to come.