“I started designing jewellery that spoke to me, because there wasn’t much jewellery I wanted to wear…I wasn’t really sure where it was going of course, but I knew it would find its place” reflects Jacqueline Rabun in the first of two Zoom calls in which we discuss her three decades and counting career in jewellery design. Immediately evident in her opening answer is the power of intent married with application. The impetus for designing began with her, she was neither creating with an ideal client in mind or at the mercies of a ‘market’ to court or appease. This unapologetic approach has brought dividends although not without challenges along the way. Rabun is motivated by a passion and desire to actualise an alternative design offering, one that is rooted in her own experiences and values. It is this distinct point of view that has seen her contribution to the jewellery world not only unequivocal, but also a catalyst for opening the doors to wider participation in the industry as a whole.

Of course, it is easy to eulogise from the vantage point of a career of her length and breadth which contains within it the ‘holy grail’ of commercial success, critical acclaim and continued resonance in the here and now from peers and design aficionados alike. But Rabun’s is a story that is first and foremost anchored by jewellery that found it’s way onto the bodies of many and intriguingly varied clients; from rock stars and supermodels to business leaders and members of royal families all over the world. Coupled with this is her prodigious work ethic and a tenacity that hasn’t let setbacks, curveballs or racism, derail her from her goals. Rabun is softly spoken, with an accent that sits squarely in the mid-Atlantic but without any of the international-jet-set affectations that many have come to associate with such. Dressed in a deceptively simple yet perfectly cut white tunic, her hair pulled back, skin clear and eyes animated, she appears the embodiment of a woman seated confidently and elegantly in her power, who hasn’t been discombobulated by the uncertain, pandemic ridden times we are all living in. When I note this she laughs: “I carry on as I always have” which for her is working largely from home as she straddles her work for her eponymous brand and her long term collaboration with Scandinavian heritage jewellery house, Georg Jensen.

An Autodidact Finds Her Voice and Place

Rabun surprisingly did not train as a jeweller: “I studied fashion design at the Fashion Institute in San Francisco, that was the world I always thought that I would be a part of… My mother taught me to sew, and I actually knew how to cut a pattern and make my own clothes from a really early age. But as I was studying fashion design something came over me and I felt as though this wasn’t my world anymore… the fashion industry is amazing but I guess I was quite sensitive at the time…so I stopped and by pure accident I started working at a jewellery gallery, a very beautiful one in Los Angeles , called the M Gallery and it was like no other space I had ever been to.” In many ways the M Gallery was the perfect training ground for Rabun’s own as yet conceived design practice. Proprietor Michael Dawkins had a curatorial approach, with collections by jewellery-artists, architects and other interdisciplinary practitioners that didn’t fit the classic high jewellery mould, finding a home in his destination space that attracted an eclectic clientele who were drawn to contemporary and directional pieces. At home, inspired by what she saw, Rabun started experimenting: “I started teaching myself: first how to design and then how to actually make. I am a better designer than maker, but I can do it if I have to” she adds laughing.

Romance precipitated a move to London in 1989 and it was here that her processes and her ideas solidified. Her first collection, Raw Elegance, launched in 1990 was a commercial triumph with Barney’s New York an immediate stockist – unheard of for a new designer, never mind a female black one. Rabun herself is uncomfortable with using the term ‘collection’, with its undertones of ‘in today, out tomorrow’, and prefers the term ‘series’ which hints to a continuum of states and a revisiting and exploration of themes, a notion that ties in with both her first and all her consequent bodies of work. Speaking of what it was that drew in a retail behemoth like Barney’s and the slew of luxury stores around the world to stock her immediately she expands: “I think it was because it was unlike any other jewellery they were stocking at the time. It was quite masculine but there were feminine undertones. It was very organic and natural using shapes and forms that follow the lines of the body and it was just very different for that moment.” Crucially, Raw Elegance coincided with the genesis of reimagining gender boundaries in fashion and beauty and that was to be a hallmark of the 90s: Calvin Klein’s unisex fragrance CKOne, was the scent of the decade, Jean-Paul Gaultier had a mixed gender fashion show in Paris for his Spring/Summer 1994 collections and indie bands with effete lead singers such as Blur with their anthem to blurred gender role boundaries Girls & Boys ruled the airwaves. For the jewellery world Raw Elegance was an early presentation of similar ideas – themes that many jewellery brands have since explored and developed.

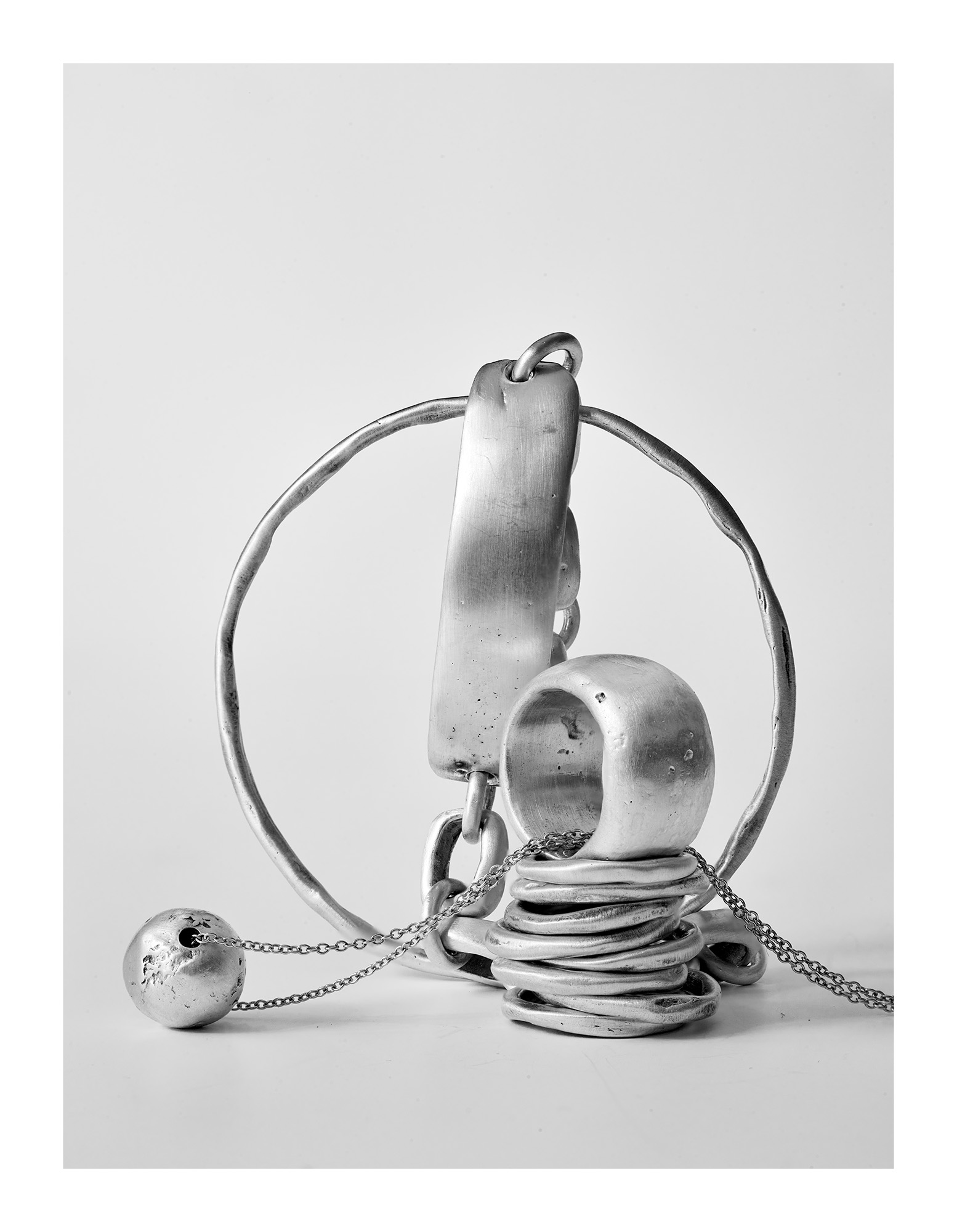

London in the 90s was arguably the coolest city on earth, with a creative renaissance not seen since the swinging 60s. It was the decade that saw the dominance of British fashion designers with John Galliano at Dior, Alexander McQueen at Givenchy and Stella McCartney at Chloe dictating how the world dressed. The Young British Artists or YBAs as they were collectively known, all featured in Sensation, an exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in 1997 that placed fine art at the heart of pop-culture. In the jewellery world, Rabun alongside Shaun Leane designed pieces that were in diametric opposition to the ostentatious 80’s aesthetic and resonated with subcultures in what was then an edgy East London and bourgeois West London bohemians alike. Looking back at the cross-pollinating and dynamic energy of the city then Rabun remarks “when I first moved to London in about a week I met Judy Blame through a friend and he loved my work, so he immediately used a couple of my pieces for Neneh Cherry.” The fortuitous meeting with the legendary uber=stylist brought her into contact with others luminaries. “It all happened very organically, I have to be honest. It was all very word of mouth because of course we didn’t have social media, but pretty quickly I was connected with a few people at I-D Magazine and I had some articles in I-D, The Face, Dazed, thinking back I had a lot of publicity” The coup de grace was landing the cover of British Vogue’s September 1992 issue with Linda Evangelista adorned in pieces from the now extended Raw Elegance Series. “I guess that was one of the little signs that were a cosmic okay, you’re moving in the right direction. Because actually when you start off in a career where you haven’t actually studied and trained and you have taught yourself, you always question whether you are doing the right thing.” From there, her star was fully in ascendant, with musicians particularly drawn to her work. Madonna, Whitney Houston, U2 and Lenny Kravitz were just some of her many A List clients. Living in London, which at the time was the de facto laboratory of new ideas across multiple creative disciplines had an undoubtedly positive effect on Rabun’s own practise.

Distilling Her Design Language

Rabun is unabashed in her love for design and it seeps into every aspect of her life. The slither of her home visible on the screen, is dotted with beautiful artwork and artefacts picked up from her travels. She relates that her passion for mid-century furniture has resulted in a considerable collection, some of which is in storage. It is illustrative of a woman for whom aesthetics across all touch points are of profound importance. But for Rabun it is more than surface level prettiness informing her. “When I speak about design language it is about the shape and form of a particular object but it is also the story behind that body of work. For me, my whole design language is about the human experience…each one of my bodies of work is definitely inspired by what I am going through in my life which is probably what everyone else goes through as well,”.In many ways the clues are there in the names of the series of work: Love Distance for instance features two rings with corresponding curves that unite when together but look equally beautiful on their own speak to a long distance relationship. And her first collaboration with Georg Jensen, Offspring, was inspired by the birth of her son: “Offspring is about the unbreakable bond between mother and child and a lot of women go through this…[and] the actual shapes of the pieces are taken from an egg form and eggs are the beginning of life, so it is symbolic of new beginnings. When you have a child your life begins anew and there are challenges but even when it is difficult you’re still in it. It is unbreakable.”

Her collaboration with Georg Jensen is how Rabun is perhaps best known. Indeed many wonder how an American based in London came on the radar of the Danish heritage house that has been seen as the custodian of Scandinavian design. As with much of Rabun’s story serendipity met with an impressive body of work, she relates “I have a friend who is in fashion and I went out to dinner with her and her partner and they invited Mark Olm who is a Danish photographer and he mentioned that Georg Jensen were looking for designers and he thought my work would be perfect and he happened to know someone there, So he basically spoke to them the next day, gave them my telephone number and we emailed but it wasn’t a thing. I got a telephone call the next day the design director from the jewellery came to see me and then gave me a brief and we were working together.” The whole process from dinner to commencing work took ten days. Astonishing by any measure. But when I gasp in exclamation Rabun adds that she views it as manifestation for both parties as Jensen were looking for someone and she too was seeking to expand her horizons after by that point, nine commercially successful years in business. Most critical to the speed of engagement was her design language which she notes “has an equal dose of Scandinavian and African influences and interestingly there is a lot of Scandinavian jewellery where you can see the designer is very knowledgeable about African jewellery.” Certainly the collaboration which commenced in 1999 with Offspring launched in 2001 and then rebooted for 2018 has been beneficial for both parties. Offspring, is as time of publication, Georg Jensen’s bestselling jewellery collection.

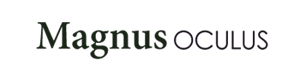

Rabun continued to plough the myriad of human experiences and emotions for other series with the heritage house. Cave launched in 2002, a series celebrated amongst jewellery connoisseurs globally who are clamouring for its re=issue, featured concave circular forms occasionally with pave diamonds in a hollowed form. It was a comment at the need to sometimes retreat and find a place for quiet contemplation and reflection. Mercy was launched in 2019 but Rabun notes “I started developing it fifteen years ago and then Georg Jensen asked kindly if they could launch it under their brand. Originally, it was designed for them but we were working on so many projects that it just never happened…but if you think about the time we are living through now it really resonates…we need a lot of mercy. There is a big need for compassion and empathy for others and to walk in somebody else’s shoes for five minutes. It is about not being selfish. It is not that moment now.” To encompass those sentiments, the sculptural forms look different from each vantage point, for both the wearer and those viewing the pieces on the wearer’s body, resulting in an exquisite metaphor for Rabun’s intention. As ever with Rabun, diamonds when utilised are done so discretely, something that some assume given her African-American heritage is unusual as African-Americans and their biggest cultural export, hip=hop are intrinsically linked with the maximalist ‘bling-bling’ aesthetic. She laughs in recognition at what is ultimately a lazy assumption: “My design language is minimalist, but actually there is a lot of African design that in itself is quite minimalist. From art, to furniture, to jewellery. As with me, there is a lot of use of organic forms and that is my link. I draw more from my African heritage, rather than the popular media stereotypes of what black glamour is. I draw more from African jewellery and African art.” It is a reflection of what for many years have been the silos of expectations creative people of colour have oftentimes had to work in. The assumption that one voice, one style, one set of experiences fits all, when in actuality, things are more nuanced and varied.

Rabun’s eponymous line has continued to expand on her thesis of jewellery that reflects, documents and harnesses the human experience. A recent special series A Beautiful Life for the PAD Fairs in London and Paris in 2018 included a re-imagined Beautiful ring in aventurine and yellow gold as well as one featuring rutilated quartz crystal and yellow gold. There was also a pendant with a yellow gold vessel form in which a removable aventurine sits, giving the wearer the choice of removing it and holding it in their hand for on-the-go meditative purposes. The choice of gemstones for these pieces was deliberate “my work always has to be honest, I have to like the stone, I have to feel an affinity with it otherwise I cannot work with it”. In the instance of aventurine Rabun was drawn to its historical healing properties which is said to aid the nervous system. Green aventurine in particular is known in the Hindu Chakra system as a heart healer that dissolves negative thoughts for the wearer. Rabun adds “jewellery can give you a sense of security [and] If you walk out of the front door without it you feel like something is missing, I think everyone has had that experience who wears jewellery, and so it is a form of armour and I think if we take that into a spiritual realm it calms you and it gives you comfort.” When we speak of her attraction to rutilated quartz, whose beauty lies in the visible inclusions that sometimes have the appearance of spun gold thread left to form a messy yet captivating pattern, she adds “When you look at these stones you think wow, how did that happen? How did all that imperfection arrive in that stone? I like those imperfections. Because I think that is what we are inside we are not perfect.” It is in many ways a radical proposition, especially as there is a whole sector of jewellery that is dependent on gemstones of almost supernatural perfection that will imbue their wearer with similarly polished, beguiling powers. Rabun is offering wearers to feel comforted and empowered but also vulnerable and open enough to show and share their authentic self rather than a carefully crafted facade. If the gemstones can be honest so can we.

Present Realities and Future Series

Whilst many creatives have been emotionally buffeted by the ‘new normal’ that Covid19 has heralded, Rabun true to form has observed the peculiar needs the season has brought with it and created solutions. “I have been quietly working on some objects for the home and some furniture.. because the home has obviously become so much more important to everyone in the world.” Expanding her canvas from the human body to a room is a natural progression. She has also used the time to reflect on how she wishes to present herself and her work moving forward. She states “I definitely prefer to be known as an artist because whilst of course my speciality is jewellery, I have designed objects furniture and sculpture.” She pauses, before adding “This word designer, I think when you have worked for a long time and you have a specific recognisable look and feel to your work it takes you in to the space of being an artist.” Her oeuvre is ever evolving, but as with many artists, it is doing so on her own terms

.

We close our conversation with a question that Rabun is initially a little hesitant to answer, “you answer it” she challenges me jokingly, and that is how would she describe the Jacqueline Rabun aesthetic. She expands “A lot might say or think that my jewellery is organic and minimal. But it is important for me that those shapes and forms have meaning. I don’t design for design’s sake. I really need to have something to say when I am designing because there is an awful lot of jewellery in the world.” Suffusing jewellery with her own spiritual practises and beliefs is of paramount importance to her, far more than sales figures or public acclaim. “I really hope my work will have some sort of a positive impact on someone’s life, whether they feel empowered or inspired or comforted or cured. Recently, a woman who had cancer wrote to me and said she used one of my pieces as a talisman to get her through her cancer treatment. To me that is why I do what I do.” None of us fully knows how we will be remembered, but for the fortunate few such as Rabun, a body of work that speaks to her truth and resonates in such visceral and powerful way with her clients, provides a validating clue.