“I grew up thinking I was not creative at all and it took me probably all the way into my thirties to overcome what I had been led to believe at school.” Ute Decker, jewellery artist and ethical jewellery activist is reminiscing about her earliest creative memories and I am surprised that there isn’t a strong biographical artistic thread. For an artist who since formally launching her brand in 2009 has experienced immense critical acclaim and commercial success with her work being described as ‘wearable works of art’ by the auction house Christie’s, and acquired for the permanent collections of both the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Swiss National Museum in Zurich, it is somewhat puzzling that there were no early indications in her childhood of what was to come. Our Zoom meeting, which takes on the energy of a stimulating conversation with an intellectually curious friend who is as engaged with the world around them as they are with their craft, doesn’t feel like ‘work’ at all. In fact, we both agree that the whole interviewing business would be greatly improved with a glass of Grüner Veltliner, a wine we discover we both love. As our conversation progresses it becomes clear that Decker is so much more than an artist or a pioneer and early advocate of ethical jewellery practises; she has that rare quality of being equally a thinker and a doer. Her sculptural pieces possess the physicality of being made by her own hand, yet her ideological beliefs are imbued in the fact that the materials she uses are wholly ethical and traceable. We discuss her beginnings, her methodology and why she hopes that more in the industry will truly embrace ethical practises, especially if the jewellery industry is to truly shed some of the negative connotations that linger to this day.

A Fearless Point Of View

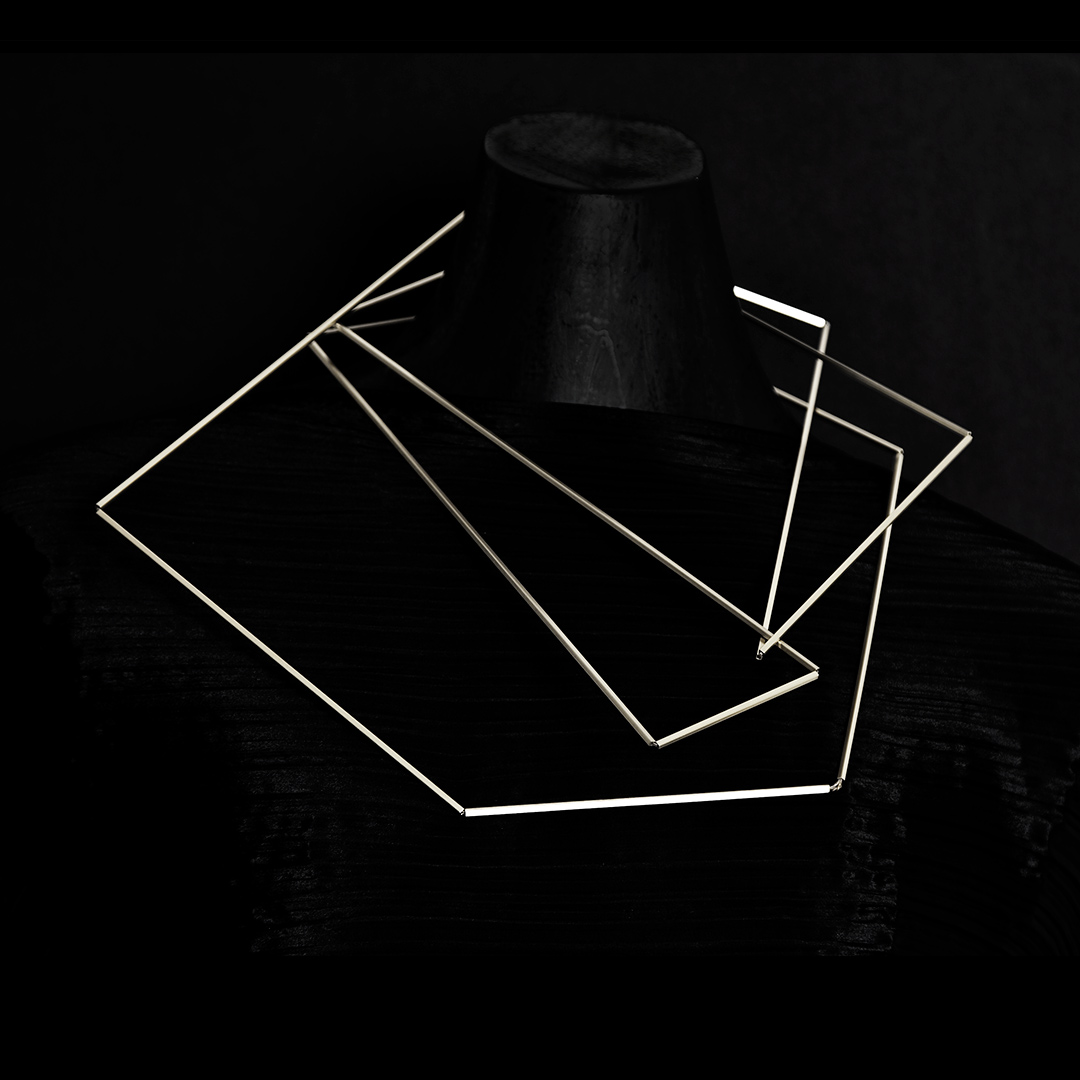

Decker is unabashed about her beginnings; she says with a smile “I used to call it ‘winging it’ but of course nowadays I would say I am an autodidact…I went to evening classes just to have access to tools.” There is a pragmatism in her rationale for attending evening classes, but it also reveals a creative who is governed by process, knowledge accumulation and self-mastery, indicative of her previous job as a news journalist and researcher. That she came to her craft, via it being a passionate hobby also allowed her a more expansive, unburdened, relationship, something that she is quick to point out: “Making jewellery for myself [resulted] in me making it stronger because I didn’t come out of university with a jewellery degree and then have to earn money. I was completely creatively free.” Then as now, her pieces are not obvious ‘crowd pleasers’ but rather require a wearer who has an equally unapologetic approach to aesthetics as Decker. Indeed, bestsellers such as the Infinity and Orbit collections sit comfortably on the nexus of sculpture and adornment, and could easily be at home on a mantel shelf as they are on a wrist or finger.

Modern life has made many industries increasingly youth focused. We have become conditioned to saving our noisiest praise for young prodigies. Subsequently, creatives of all ages lose sleep thinking of ways to capture the eyeballs online and the money in real life of young consumers. However, Decker took a different approach: first and foremost she ensured her honoured her truth and pleased herself, she adds cheerily “I made very large sculptural pieces that commercially are a complete no-no..but I already had my own character, my own language. I didn’t want to please anybody.” This approach proved critical in tapping into a powerful and oft ignored demographic “ A lot of my clients are mature strong women” she notes when I ask her about who is drawn most to her work. By appealing to women like herself she ironically reflects our contemporary love affair with ‘relate-ability’, but in Decker’s case it happened organically rather than as part of a marketing strategy. Most pertinently, it has resulted in cementing, relatively quickly a client base that is neither driven by trend or, because they statistically earn more money, governed entirely by cost. Among her early collectors was the late architect Zaha Hadid, and the former Serpentine Gallery director Julia Peyton-Jones was another admirer of her work. But beyond attracting celebrity clientele and creative cognoscenti acclaim, her work connected on a meta-level. Formally launched in a group show in 2009, and significantly after the 2008 economic crash, it reflected a global yearning for jewellery that had depth of meaning. It also came at a time when there was a desire for original voices who could create something that stood apart from the offerings in the high jewellery meccas of Paris and New York.

On Inspirations and Methodology

Decker’s atelier is situated in London’s Cockpit Arts, a jewellery and design hub tucked between the city’s historic jewellery district of Hatton Garden and the leafy legal heartland of the Inns of Court of Holborn. Decker, who is originally from Germany was drawn to the space because of its sense of artistic community in a large sprawling city. However, although self-taught her design process is influenced profoundly by principles drawn from eastern traditions: “Are you familiar with Ensō?” She asks before continuing “I try to work as with Japanese calligraphy, with the Ensō it is a circle that you draw…you have to be an apprentice and practise it for twelve years before you can put your name to it. I think that kind of practice is how I work. When I start off with the garden wire, I work until l have something that speaks to me and I am happy with and then I keep making the same piece, over and over again in brass. I work it out until I no longer have to think of the process and my hands now know by themselves. Once I have an intuitive feel, rather than doing and thinking through a lot of things, I make the final piece in metal, in one go. Like calligraphy, it needs to have that flow and dynamism and a natural end. And even if a client said I would love that brooch in gold or smaller or bigger I would still go back to the brass, to get my hands in the flow again. So it might take a few days. Sometimes the lines won’t speak to me and I will work on it for months and then just by chance I walk past a piece, pick it up, do one thing and there it is.” A process such as this is seemingly at odds with the western driven bottom line, one where a bestselling design would be churned out with celerity with the maximising of profits at the forefront of all activities. But like with much Decker does, it is challenging but ultimately rewarding. Supreme self-discipline in the repetitious nature of initial work is coupled with a spiritual harmony of intrinsically knowing when the piece is ready. As with the Ensō, the goal is mastery borne out of a lack of inhibition.

Warming to the conversation on eastern philosophies and beliefs she continues: “I am very interested in Zen Buddhism and I have tried meditating but I am not a practising Buddhist. In Zen, it is very much the idea of creating with an empty mind. So I sit there without any preconceived ideas. Without thinking, without an aim and without a goal for the end. My work is much more about a sentiment or a sensibility so I never have a concept in mind before, it is only later something might come.” She also invites her collectors to embrace a similar notion, where preconceived ideas are left at the door and instead they engage with a piece ‘empty’ and wait to respond to the emotions it might elicit. It is poetic and places Decker’s work more in the jewellery-artist category than the conventional jewellery designer. Of the distinction between the two she adds: “I don’t say I am a jewellery artist because I feel it sounds slightly pretentious. I tend to say I make sculptural pieces…or I hold out my hand or my neck and say, that is what I do. I try not to define it…If you consider that art it is art if you consider it jewellery, it is jewellery. It is about bringing your own perspective.”

Perhaps because of her circuitous route into jewellery, Decker steers away from labels or classifications being applied to her work. When I ask her of influences she pauses before responding “I admire the Padua School who are also quite minimalist but I don’t see myself as part of an artistic creative or jewellery school. But I would see myself as part of the ethical jewellery movement.” The Padua School under the unofficial leadership of Mario Pinton were at the vanguard of experimental gold smithery in the 1950s and 60s and like Decker, members such as Giampaolo Babetto were drawn to creating exploratory pieces that could be seen as both sculpture and jewellery with a minimalist sensibility. Intriguingly, the Japanese writer Jun’ichirō Tanizaki also provides ideas that fuel her work: “I have read‘In Praise of Shadows’ by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki and although it has several political issues there are certain sentiments in the book that I agree with. Tanizaki describes how when you go into a Japanese house it is so empty but then the play of shadows is so powerful. Something so minimalist: the wind rippling through the trees, a gentle wave rolling in the ocean, looking into the fire…Those are the simplest smallest minimalist experiences…and because the process is so condensed and reduced that makes them the more powerful.” Relating it back to her practice she concludes: “I think quite often with jewellery people are thinking of where can they put another little diamond or another little swirl. For me, when a piece is done I am thinking what else can I take away to make it less busy.” This doing away with, condensing, distilling, until, one is left with a piece’s true essence is at the heart of all of her designs.

The idea of embedded energy is another concept that for Decker has great resonance, citing Alexander Calder she expands “…what really gives me joy looking at his work is you see little images and videos of how he makes things and that joy that he brings across. And every time I look at one of his pieces I see that maker’s smile.” Making and the physicality and personality she brings to pieces is what posits Decker’s work most in the jewellery-artist category. “My hands think in three dimensions so I need to actually make and experiment” she says adding “I never draw anything. I couldn’t draw this (she gestures to her wrist, where she is wearing an iteration of the Orbit bracelet),…I just play and experiment and by the end of it something completely different will fit.” She is happy to see her pieces as wearable sculptures but it was only when the opportunity of making a large scale piece for a client came about that she realised how wedded she was to her particular process: “It was a wonderful budget and I thought ‘Yeah, I always wanted to make larger sculptures and here is an opportunity, someone is commissioning me!’ But I must say that the process was less satisfying because I had to hand it over to a fabricator. I was no longer the person…for me it is really important that my hands, that I am involved, it is that joy in the creative process.” Just as with Calder, her energy, her essence, indeed her joy, are intrinsic to the completed work. “I don’t think I am a designer because it can’t be replicated. I can’t give it to someone else never mind do so myself.” Again, she resists easy categorisation: “I actually find it very difficult with the nomenclature thing as well, and it seems to be [more about ]what people are thinking.” And as already explored Decker is loath to allow external gazes to qualify or quantify who she is or what she does. She smiles before finally conceding “Jewellery artist is probably the closest term. There is an artistic expression. There are some thoughts and constructs and concepts that while not at the beginning of my process are certainly part of it…that is probably the main reason I would say jewellery artist. But I am definitely also a maker.” Indeed, her work is represented at one of London’s most renowned galleries for jewellery-artists, Elisabetta Cipriani.

Activism and Jewellery

Jewellery was never going to be just about adornment given Decker’s background. “I am very politically interested, I studied Political Economics at the University of Hamburg, lived in Paris, and spent some time at the UN in Vienna and was involved with the climate talks” Unlikely to content herself with trotting out superficial statements to her conscience or her clients’, Decker wanted to ensure that her jewellery was as equally imbued with her values as it was with her aesthetics. She expands: “Being part of a bigger picture, working with fairly traded gold, being part of the whole earth and community is important to me. I don’t just want to make art for art’s sake. I like to express certain sentiments but also be part of the solution of the issues that are important to me…When I studied there was a whole course on the meaning of work. Who am I in this world? How do I fit in? Do I fit in to the anonymous production or do I want my work to be more meaningful to myself and to the greater context?” It was these questions, coupled with her news journalism background that prompted her into deeper investigations on ethical mining, sourcing and production. The private endeavour resulted in a rejection of using gemstones: “The Kimberley Process ( the global agreement that came about in light of negative publicity on so called blood or conflict diamonds) is not worth the paper it is typed on. There are no ethical diamonds, there are no fair trade diamonds, there are some that are better than others like Canadian diamonds with more traceability, but…” She trails off and shrugs, incredulous that the general public has by and large swallowed the notion of ethical diamonds when many gemstones for the most part, still come from parts of the world which have either historically or are currently in the midst of political, socioeconomic and human rights tumult. It is for this reason that Decker herself continues to not use gemstones in any of her collections and subsequently focused her investigations on precious metals.

We alight on the first online ethical jewellery directory that she created, that was previously housed on her brand’s website but now has a permanent home on ethicalmaking.org which is a partnership between Decker and the Incorporation of Goldsmiths, Scotland, she adds: “Metals have an incredible footprint, it’s an incredibly dirty business whether it is from the environmental perspective or in terms of human rights and exploitation…It’s an absolute horror story. And when I read about that horror story my first reaction was ‘Oh my God, I cannot be part of this. I cannot use these materials.’ Surely there must be some gold or some silver that has been mined in a more environmentally friendly fashion… I didn’t start off thinking I am going to build the world’s most comprehensive ethical jewellery directory. It was just one piece after the next piece…I put it all online and that opened up conversations.”

This is not to say that her activities were met with universal support within the jewellery community. In spite of sustainability and ethical having recently not so much become buzz terms as mantras that all must adhere to, there was push-back. Reflecting back on those early beginnings she relates: “I talked to other jewellers and some of them were like, ‘Yeah, I might be interested.’ But at the beginning there was a lot of hostility from other jewellers because once you start talking about ethical you open up a can of worms…. If you say ‘ethical’ [jewellery] there must conversely be unethical jewellery. So the jewellery world didn’t like it.” Of the ongoing trend for jewellery houses both small and independent and large conglomerates to tout their ethical credentials she warns that consumers should be “aware of ‘greenwashing’, which I now think is the biggest danger… what we have now is a proliferation of claims and the Responsible Jewellery Council which already sounds fabulous and if you go on the website you would think you were on the website of Greenpeace… but in fact it is just an industry association…all the big mining companies and a lot of the big diamond companies are in there and now everybody says ‘our diamonds are sourced responsibly Kimberley Process and our metals whatever are also responsibly certified or we are getting it from a Responsible Jewellery Council source.’ Both of them are utterly meaningless but as a consumer you think ‘Oh, fantastic all of them are sourcing ethically.”

Clarity of information is something of particular importance to Decker who in addition to her jewellery practice lectures and continues to lobby for greater traceability of where metals are from for both creatives such as herself, seeking to be ethical in their sourcing and consumers who want to be assured that what they are choosing to purchase is truly ethical. On her own journey one pivotal connection was with Greg Valerio an agrarian, artisanal mining and ethical trade activist. “Someone told me about Greg Valerio who really is the hero of the whole story. He comes from a human rights background and started an ethical human rights shop…. he also found out about a small mining co=operative in Columbia called Oro Verde – and they worked on the same values and principles such as re-foresting and such… And then he went to the Fairtrade Foundation and said ‘guys you must get on board, we must have something certified…because there are so many ethical claims’. So that is how the first fair trade gold came about.” Decker is also eager to qualify the difference between Fairtrade and fair-trade, something most consumers wouldn’t immediately differentiate between; “It is also very important to note that the word fair trade with a hyphen or small letters is not protected. But Fairtrade one word and capitalised is…Fairtrade standards involves women’s rights and also economic rights, strict environmental standards and the money is invested, so we are paying a fair price but we are also paying a Fairtrade premium. And that premium the community can then decide what they need….So it is the community that jointly decides what they need most. It is investing in schools and people need to understand it is not some kind of ‘aid’, it is paying a bloody fair price.” Her and Valerio continue to raise awareness and campaign, often appearing on panels together.

Empowerment, Conscious Consumption and Future Plans

For Decker empowerment does not stop with elucidating stakeholders of the ethical jewellery movement. It also comes via her invitation to wearers in the co-creation process. “I give my pieces relatively abstract names. I have a thought of what they make me feel or what they remind me of but then the title is abstract enough to invite others in.” She uses her collection Orbit to illustrate the point asking me what I think it reminds me of before concluding, “So when I said orbit, I was thinking in terms of the solar system but you were thinking of chemical elements and atoms and that is beautiful…individual empowerment and individual expression combine in my jewellery.”

Occasionally, with her private clients the tables will be turned. She reminisces, “There is one wonderful collector in New York who commissioned me for a piece…her brief was ‘wild and abandon’ but I have to be able to type in it’.” The process took a year but it was precisely because Decker had a plethora of ideas that she explored fully before settling on the one that she felt was best. Inevitably, she returned to her eastern philosophical principles adding: “There is a concept in Japanese philosophy aesthetic called Ma, which could be translated as emptiness…for us in the west emptiness is a negative. But the concept there is if it is empty, it has all the possibilities opening up.” Allowing time to be inspired, to play, to dream and ultimately make are key in her creative process, as she waits on ideas to have their full fruition. Clients in turn are encouraged to exercise patience and trust that the beautiful synergies and work will emerge. It can also ultimately result in a less exhausted earth as we are all forced to consume less and not expect every desire and whim to be met immediately.

As our conversation comes to an end I pose to Decker whether she sees jewellery as another pit-stop in her portfolio career or the arena in which she intends to stay. She pauses before responding: “We could say jewellery is totally unnecessary, we have enough stuff in this world and with the materials and the issues, do I need to make jewellery? But I think making very few pieces, making pieces that count, that are not just in and out of fashion before you can blink, is worthwhile. Sometimes clients come and say ‘oh yes, I bought this at your very first exhibition and I have been wearing it all the time’, and hearing that gives me so much joy.” Decker has a mind that is so agile and a seemingly insatiable curiosity and desire to share knowledge and beauty, that it feels unlikely that jewellery in and of itself will be an adequate framework for what. Has already been a considerable body of work. However, jewellery redefined and deconstructed within her broad locus of concerns and passions has become a much more nuanced proposition in and of itself. All creative disciplines need a dose of disruption to truly evolve, Decker is doing this for jewellery one sculptural, beautiful, ethically produced piece at a time.