“Gosh, I don’t even want to consider the word success. I think I’ve just started, I probably haven’t even started yet. It takes a long time to build a maison and a fine jewellery brand especially.” It’s a late Friday evening interview over Zoom and Satta Matturi, founder of Matturi Jewellery, is being either a mistress of self-deprecation or a Herculean task master, depending on one’s perspective. Whilst other houses have barely fumbled through the post=pandemic uncertainty that has gripped many in the fine jewellery and to a wider extent luxury world, Matturi Jewellery has grown an already enviable client list, embarked upon a glossy rebrand and participated in not one but two ground-breaking selling exhibitions curated by the art-jewellery maven Melanie Grant: the first, Sotheby’s New York Brilliant and Black exhibition in September was a historic watershed for black jewellery creativity, the next the forthcoming Forces of Nature exhibition at the Elisabetta Cipriani Gallery later this month in London, promises to cement the house in the canon of highly collectable jewellery-artists. When I reflect this back to Matturi, she shrugs and insists that despite all the laudatory noise be it online or in real life, this is not a lean back and pop a bottle moment, “This is when you start to work.” And ultimately, she is right because plaudits and attention are only as good as their utility. As our conversation stretches into the night it becomes clear that Matturi has goals that are far-reaching and are about profundity, productivity and shifting centuries inaccurate perceptions of African truths.

A Family Affair

Thinking back on her formative experiences with jewellery brings Matturi to her childhood and her parents in particular: “My Mum actually wore a lot of jewellery… And in west Africa we wear a lot of gold. And it is not even your 9 carat, 14 carat we are talking 22 carat and 24 carat gold.” Add to this a father who paid a pivotal role, first creatively: “My Dad was an architect, so that is where the creative comes in. He studied tropical architecture at Howard University in the US in the 50s.” and secondly as the catalyst to her exposure to the diamond industry: “He was involved in politics and later was Managing Director of DeBeers for the West Africa operation in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, for twenty one years” she reminisces and Matturi’s journey into the jewellery industry feels predestined. Her home was a practical storefront to the mechanics of the mining industry. “At the time Sierra Leone was one of the most profitable producing countries for the company and I grew up in a house where I saw it all: we are talking paperwork, we had the valuers coming in to look at the production and the shipping team would come through. And I was there. I could see all these bright lamps, it was part of life and growing up.” Matturi followed her degree in Business Management from London Metropolitan University with a place on the DeBeers graduate recruitment training scheme “it was tough because it was two years of head down and learning about diamonds. I think it is one of the best things I have ever done” and thus began a career where she rose to be one of the most highly regarded rough diamond experts in the world.

Having an extensive knowledge of rough diamonds and an undeniable emotional connection with jewellery courtesy of her mother’s collection informed both Matturi’s entry point and continued engagement level in the fine jewellery world. Of the former she notes “I have a consultancy, so I still keep my hand in. 60% of what I do is on the rough [diamond] side but at the top of the value chain [and] it is so nice that we are having this conversation because people don’t know that about me.” However, it is her time at DeBeers that prompted her to reconsider or rather expand her contribution to the gemstone industry. Prior to leaving she notes: “I worked as a key account manager looking after huge, massive clients. Tel Aviv, Hong Kong, Mumbai, New York, Antwerp, it was all happening for me. We are talking turnovers of – well Tiffany’s was my client who I managed for years… And then I don’t know, I thought to myself there is no-one out there that makes jewellery that looks back to where a large majority of where the raw materials come from. Not a Graff, not a Cartier, not a Bulgari not a Chopard, none of them. And then I started making stuff for myself, for friends and family.” This seemingly low-key beginning precipitated into something more concrete when DeBeers instigated a large move of operations to Botswana. Matturi’s spouse (also coincidentally a DeBeers director) stayed on while she resigned and used the relocation as an opportunity to launch the business in earnest. Her calling card was being in possession of legitimate professional receipts that would allow her to navigate the diamond and coloured gemstone business. Meanwhile her unique differentiator would be a passion for African storytelling and artistry. “I didn’t just drop into this I know it.”

The Diamond Lady 2.0

“They call me the Diamond Lady” Matturi says with a hearty laugh. However, hers is not a case of a career built on the back of pedigree with a side order of passion. Whilst Matturi leveraged her extensive gemstone industry knowledge when she was building her brand, she has also used it latterly to educate clients, particularly those who might be suspicious of her sourcing practices. For the doubting Thomas’ still stuck in a negative thought loop that equates her Sierra Leonean heritage with conflict gemstones and war atrocities she elegantly counters: “I actually buy the rough diamonds for the manufacturer who cuts and turns them from rough into polished and sells wholesale into Cartier. I sit in the diamond office and the Cartier buyers come into buy. The Messika buyers get their diamonds from a company that I consult for. So basically, it is the same stones that are going into my jewellery.” The casual mic drop resonates on many levels. Unconscious bias, or it’s uglier relative, systemic racism, particularly in the luxury sector may still exist, but Matturi by virtue of her background and exposure to said world chooses not to dwell on the semantics of people’s behaviour.

Her brand’s existence also challenges customers, particularly those based in the global south who would not question anything they were sold in the Place Vendôme or Old Bond Street from a European or American heritage house but are reluctant to patronize an independent fine jewellery house that has a black woman at its helm. As Matturi elaborates “we don’t trust what black people do…within the fine jewellery space, we have a long way to go. And it is not just me…other jewellers feel the same. So even with the Sotheby’s thing we just did one of the questions I asked was ‘where are all our black philanthropists when we need them?’ So, I sold, I sold two items and they were bought by white people. Where is Oprah Winfrey for example? Where are our people? Why aren’t we supporting ourselves? And it is not to say that they can’t afford it.” Matturi’s comments are pertinent because a lot of the discourse about inclusivity has failed to address black people, be they rich or poor’s own colonized mentality and mistrust of one another. A condition that leaves us innately suspicious of the credentials, quality and professionalism that another black person can provide, or that seeks white validation as a preliminary requisite before we support individuals, businesses or artists of colour. It is a complex issue but speaks to the heart of luxury where items perceived value and aspirational status are inextricably linked with the maker or designer’s reputation and brand capital.

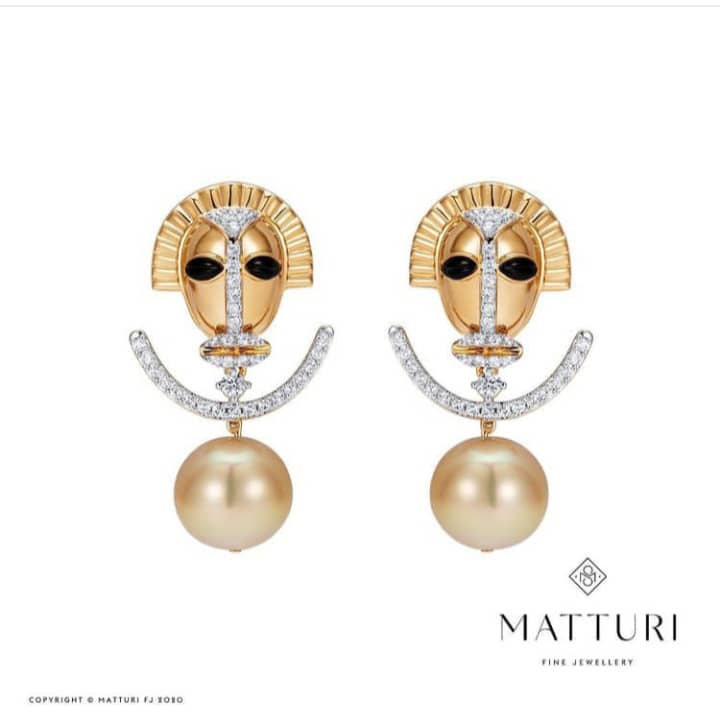

Matturi’s quiet and conscientious approach, which is at odds with modern mores has so far paid off dividends. “there are lots of things I don’t talk about – we’re stocked in a little gallery shop in the Place Vendôme and they also have a store in Gstaad.” As well as the very high profile patronage of Rihanna who is frequently photographed wearing her Nomoli Totem earrings, clients are drawn from the world of art, spouses of industrialists and lifetime members of the world’s 1%. “We’ve been on the super yachts in Monaco, we’ve been on the private jets, we’ve done it all, [but] It is a completely different space and you have got to keep on working at it.” Matturi doesn’t take anything for granted and knows that with the more commissions come greater expectations, a challenge she fully relishes. “If I have stones, I am like right we are doing something crazy. And you can send it to a client, they wear it for three or four months and they fall in love with it and then they go right let’s buy.” Matturi is in the business for the long haul. She understands that a maison that outlives its founder must focus on the craft, both resonates, is timeless and is not driven by trends. Finally, perhaps most important is that the high jewellery world operates in similar ways to contemporary art. Collectors and artists often interact, work might be bought as an investment but it also becomes part of a family’s heirlooms, and most pertinently, because it is worn, there must be an emotional connect.

African Semiotics, Craft and Material Choices

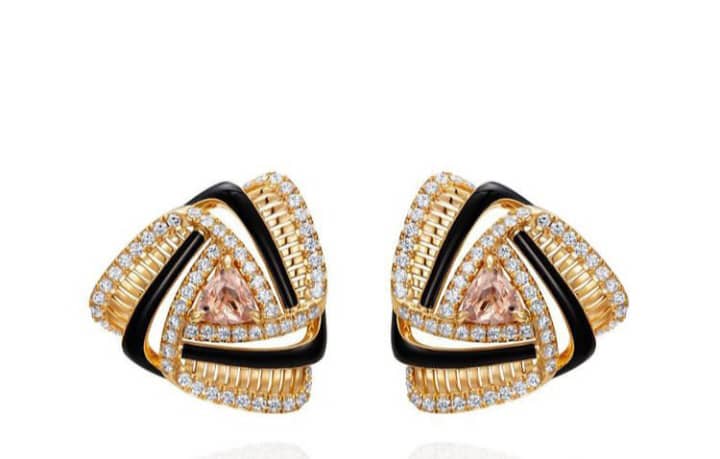

“Everyone has been doing Egyptian jewellery but no one has thought of going further up the Nile and talking about the 25th Dynasty and Nubia.” However, Matturi did. Creating the Whispers of Meroe series she took as her starting point the Kingdoms of Kush, that neighboured Egypt and which seemingly merged during the 25th Dynastyy when Kushite pharaohs ruled Egypt. Apart from the pharaohs getting more melanin in their skin tone, Kushite innovations included modified pharaonic headdresses, a bellicose and ambitious polity intent on expansion and an active restoration of traditional religious practices, architecture and art. However, the Whispers of Meroe series is neither a tribute-act to antiquity nor a lazy pastiche. In a creative sleight of hand worthy of the father of semiotics, Roland Barthes, it is in fact an exquisite African imagining of Art Deco. Matturi explains “my favourite can I say genre of jewellery is Art Deco. And I wanted to do Art Deco but I didn’t want to follow the norm, everyone does the same old thing so I had to interpret it with an African twist.” The twist, like in the best cocktails segues the familiar with an exhilarating element of surprise. Thus strong geometric patterns are witnessed in pieces such as the Nomoli Totem Obelisk earrings. Bold colourways are present in the Ta-SETI earrings and the use of monochromatic materials are evoked in the Kandake earrings which feature onyx, platinum and diamonds to stunning effect. For Barthes, signs are best understood in light of how they are interpreted by different cultures and societies. In her series, one which she sees as a continuum that she will return to, Matturi dares to and succeeds in interpreting European Deco Motifs and symbols (which in turn borrow much from the geometry of antiquity) via the African gaze. Nomenclature plays an important part of the process: Kandake was a Queen, Thebes the fabled Egyptian city and Bayuda a desert situated in Nubia.

Matturi embarked upon extensive historical research for the series, mindful because although African her cultural roots and principal reference points lie in the western part of the continent and “I didn’t want to appropriate”. However, her noble intentions hit a roadblock when overtures to Sudanese historians, writers, academic and cultural institutions drew a blank. She relates; “I just wanted someone to be on this journey with me…and no one was interested and I don’t know why. So where did I go the Met Museum, the Smithsonian Museum and the British Museum.” In many ways the latter institutions would arguably have superior resources and more comprehensive collections of artefacts, but for Matturi ownership of our stories whether manifest in jewellery or anywhere else is an important and critical endeavour. Response to the collection has been in many ways the best of her career so far, but it also speaks to her greater ambition of altering perceptions of Africa not just from external eyes but internal ones too as she notes “As funny as it may sound, success to me would be going back to my business plan that I wrote at the start and seeing high net worth Africans buying from me, pushing the boundaries and creating something out of my comfort zone.” In Whispers of Meroe, Matturi has created a series that not only possesses the scope of creative ambitions but also has the emotional and cultural appeal to achieve this.

Craftsmanship has been a cornerstone of Matturi’s process. She works out of three ateliers and it as much a reflection of her peripatetic lifestyle as it is her seeking the very best in class. She is reluctant to describe herself as an artist in the purest sense, “Oh my God, do you know what when I started out, because I am my name I say I am an owner slash creative lead. That’s what I say I am. Everything doesn’t happen just because of me – I have got a team behind me. And I absolutely love my team.” In London, the lead in her atelier “is ex Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. He used to do all the Van Cleef Objet d’art and he is just insane. So I get him to do all of my one off bespoke pieces. The earrings we just worked on we have been in the making for eighteen months.” As with anything where the stakes are high emotions occasionally fray: “We work on it for a little bit then he gets pissed off tells me to piss off and I tell him to piss off and then we come back together and its hunky-dory.” Matturi says with a laugh. But it is her collaborative approach, sharing the peaks and troughs that keep her ateliers running smoothly.

Talk returns to gemstones and material choices in general. Lab grown versus real diamonds, ethical sourcing of coloured gemstones, navigating the plethora of options in the precious metal sphere and of course communicating those choices to clients are all up for discussion. “Now we’re really deep diving because sometimes I tend to keep my thoughts to myself , okay, let’s go… I have been approached by the Leonardo DiCaprio funded company , Diamond Foundry and many other lab grown diamond houses, it is the biggest thing out there and it is just going to grow exponentially for the next ten twenty years… and it was very tempting because here we are talking about a 1kt VS2 diamond, natural will probably cost you what $13,000 lab grown is a $1000 a kt, so it is very lucrative if you are a jewellery designer. You can create wonderful things right? But I don’t want to do that, I am not into that game and that is because I believe the communities largely depend on mining. Whether it be large scale mining, whether it be artisanal mining, whether it be the unscrupulous people who go and bribe and what have you – that’s a separate conversation we can have. If we take mining away, what do we replace it with? And it is not just like large countries like South Africa, Namibia and Botswana let’s look at artisanal mining in Sierra Leone people are poor and they rely on that.” The lab-grown lobby have gained traction in the main because of costs and also by cleverly attaching their messaging to conversations around the environment and the climate emergency. Yes, all gemstones and precious metals are finite resources but take away that income source from people and one faces a socioeconomic crisis of cataclysmic proportions, particularly in the global south. For jewellery purists, there will always be the pull of stones that have formed naturally but long term solutions for the long term the human capital consequences have yet to be conceived in a holistic manner.

Matturi is quick to point out that sourcing is far from straightforward. “There is a lot of talk about the diamond industry being opaque…but I didn’t realise how opaque the coloured stone industry is. It is insane with lots of dodgy people involved.” Issues vary, but one of the worst from an African perspective is provenance not being clearly stated; “I was in Hatton Garden and I said, ‘Ooh where is this sapphire from?’ And they replied ‘it is from Africa’. And I said, ‘Where in Africa, where?’ So I had to quiz them and a lady went to the back and she went ‘Oh, all our sapphires actually come from Nigeria.’ Then label it as Nigerian. People need to know this. So I push that a lot.’” Whilst nations in other parts of the world have been able to capitalize on their supposed superior quality coloured gemstones – from Colombian Emeralds to Burmese Rubies and Sri Lankan Sapphires, African nations with coloured gemstone reserves have largely not. Matturi is searingly honest about her sourcing “there are a lot of people rushing into recycled gold I don’t do that because it is far too expensive for what we do.” Equally she resists the temptation of mistruths to create sexier copy for journalists adding “There are a few big designers out there and I’m not going to snitch as my son would say, who when giving interviews will say ‘All my diamonds actually come from Botswana’ when that’s a big lie because the size of diamonds they are referring to isn’t manufactured in Botswana.” Instead Matturi chooses to shift the dial incrementally, returning to the head-down approach of her graduate traineeship days. “It was hard to find a supplier but I found one… they are part of the Coloured Gemstone Association we know where they are coming from and they are ISO certified and a couple of companies like Pomellato buy from them… We are a long way, but we are closing that gap. the next thing I am planning to work on is pearls. We use South Sea Freshwater Pearls but like I said to you I am being honest, I haven’t done that homework yet, it is my next one to do.”

Beauty and Belonging

There is an unabashed pulchritude in Matturi’s pieces, making them immediately beguiling. Her break-out series Artful Indulgence was a beautiful and evocative hymnal to Africa with inspiration drawn from the natural world and the more domestic such as waxprint fabrics that are worn across the continent. Yet when one looks at Matturi’s body of work it comes as no surprise that she is a great admirer of Viren Bhagat, the Indian high jeweller whose pieces have granted him the status of a living legend Speaking of a visit to his atelier that she took whilst still in her role at DeBeers she notes “It completely blew us away. Emeralds that were the size of a boiled egg and set in the most exquisite way… he puts a lot of thought in what he is going to do….They take a year or two to set one 10kt pink heart shaped diamond…he bonds in with the design and the stone and I think maybe I do practice that too.”

Her considered process is one of the many reasons Matturi’s pieces are expensive. But she is quick to note that economic inclusiveness, granted at a relative scale is at the heart of what she does. “Jewellery that you keep in a safe or on a plinth, I am not one for that. I would like mine to be worn. I don’t want it locked in a safe I want people to connect with it.” With this in mind, Matturi shares an exciting new development – a diffusion line, launching in 2022, that will allow those of modest means to explore and enjoy her design universe. As ever with Matturi, her experience working with jewellery behemoths and alongside high-end independent houses came into play. “Even the wonderful Messika has got something in her stores for $800. So there is nothing stopping me, it is all about how you position it.” But this is not to say there will be any compromise on quality of materials or a dilution of her design language. She asserts “It will still be 18 carat gold, the same natural diamonds but we will do very clever designs and this time I am experimenting with ceramic. The ceramic allows us to play around and it is very hard wearing. And I’ll tell you what, I have been quite impressed with the prototypes that have been coming out” she adds with a smile. The move is also one that will appeal to younger and more fashion savvy clients, who like layering pieces, accessorizing in a more directional way and consuming luxury with carefree insouciance. It is also a canny means of future proofing the business, insuring the maison does not get associated with a specific demographic or era.

For Matturi, expanding participation goes beyond customers and includes to the workforce itself. Since her spouse’s relocation took the family to Gabarone, she immersed herself behind the scenes in changing workforce configuration. “I work with polishing factories in Botswana and I sit on the board of two of them. I project managed the opening of one of them where I pushed the case for women. So, we now have women polishers, women polished diamonds.” Not content with tackling gender parity she moved onto less able-bodied personnel. “I specifically pushed for speech impaired and hearing impaired employees. In fact our blueprint is being used by DeBeers now because they want to start employing physically challenged people into their business. But yeah, we’ve brought them in and I have sat in all of the recruitment the HR manager brought in a sign language interpreter and stuff like that and I will tell you what? Their productivity levels are way up on an able bodied polisher..I push things like that because I am very passionate about fairness.” Mention of this is non-existent on Matturi’s social media and website and when queried she swats the enquiry away. “We grew up seeing that” she adds in reference to her late mother’s extensive philanthropic efforts in Sierra Leone, but when pressed she adds “Someone else told me ‘you don’t talk about this’ but I believe that if you are doing something good and it feels good I don’t think you need to shout about it.” Matturi’s modus operandi is in direct opposition with the modern malaise of virtue signalling. Her motivations are not being fuelled by the echo loop of praise online that constant documentation of ‘good works’ results in. A single image of female cutters on her website hidden in the ‘provenance’ tab is the only clue to this groundbreaking activity. There is an old-school noblesse oblige quality to it; being the change rather than shouting about change, getting results rather than chasing likes and ensuring long term positive outcomes rather than a buzz before the feckless social media crowd moves on to the next cause. As with the charity work sponsored by Matturi Jewellery itself (the maison also sponsor a football team in Matturi’s native Sierra Leone), Matturi is drawn to measurable and time bound activities. “It is not huge but we’re doing it in small bite sized chunks. We do our youth oriented work meaningfully and I hope it does, I really do.”

Meanings, Value and Aspirations

From the beginning of our conversation, it was clear that Matturi’s goals were not linear, but rather multifaceted. “I am a very spiritual person… but what drives me [and] I don’t know how you write this is showing people out there that a person of colour can actually run a proper fine jewellery business, that keeps me going. That drives me-“ She pauses before adding “and excellence I think that is the word I am looking for. I think being excellent and presenting a business and a brand out there that is just as good as what the others are doing.” She smiles as she recalls her original website which included African capital cities in the footer rather than the oft writ = Paris, London, New York legend, but it is again a subtle and important marker – there is life and wealth and sophistication beyond the global North. When the challenging days arise she says to herself “I am going to think happy thoughts and I am going to nail it.” Most poignantly is her late mother’s entreaty to “Just keep on pushing. When you love something and you are passionate about it you are halfway there anyway.” However, Matturi is ever mindful of commercial viability avoiding creating too many high six figure pieces “I like to keep in the sweet spot where people can buy it” and anchoring her legacy ambitions with profitability “Let’s be honest the bottom line has to be speaking to me too and not just the jewellery.” Matturi’s ebullient pragmatism is refreshing in an industry that can often be awash on people focused on the esoteric and conceptual. Create by all means, but better yet, create anchored in lived realities.

Who decides what jewellery means and is? Like many artistic endeavours that are rooted in the human experience, the answer shifts and evolves across centuries and is contingent on who one is asking. Contemporary conversations are focused on positioning jewellery as art and there are strong arguments to support this thesis. Others will still assert that jewellery is strictly adornment; but even that statement requires further clarification: is the adornment for beautification purposes? Spiritual raiment? A prop to bookend rites of passage? An outward expression of an internal emotion? A lucky charm? A cultural delineator? Or is it merely the best portable form of equity one can get their hands on? “Mum always used to say to us, whatever you do, buy jewellery, buy gold…because you can always grab the jewellery, grab your kids and off you go…a lot more women need to do that , it’s not just about handbags, it’s a store of value.” Certainly, in this post pandemic era we live in, gold and gemstone prices have remained remarkably stable compared with foreign currencies and a great deal more appealing in the wearing. But where Matturi excels is in the fact that she has managed in less than ten years to create a jewellery house that responds to all of those aspects and more. The 21st Century Maison has to work beyond the business of pretty. It must have a higher purpose. Matturi Jewellery with its self declared mandate of distilling African narratives, celebrating craft, expanding participation and championing equitable mining practices, has not only understood the assignment – it has mastered it.